Shima Art Company

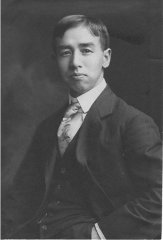

The History of My Grandparents' Businessby Kotaro Sumii1. The Founder: E. T. Shima Torazo Shima was born in Kobe as the second son of Gisuke Shima in 1877.

The Shima were a wealthy family of Kobe who had accumulated a remarkable collection of ukiyo-e prints.

As the second son, Torazo would not have been able to inherit the head position in the family,

so he moved to the U.S.A to establish a business, using some of the ukiyo-e prints as capital.

Torazo Shima was born in Kobe as the second son of Gisuke Shima in 1877.

The Shima were a wealthy family of Kobe who had accumulated a remarkable collection of ukiyo-e prints.

As the second son, Torazo would not have been able to inherit the head position in the family,

so he moved to the U.S.A to establish a business, using some of the ukiyo-e prints as capital.

At first, he lived in Nashville, Tennessee, where he had a shop and also studied political science and economics. In 1905, he moved to New York City, at 114 East 23rd Street in Manhattan. Working out of his home, he exhibited his ukiyo-e collection in various places, including Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts, Queens Borough Public Library, and St. Paul Institute of Arts and Sciences, gradually building a reputation as a Japanese art dealer.

In 1918, he married with Kazue Nakamatsu, but they had no children. Because Kazue did not tell a lot about Torazo to her posterity, little is known about him. However, we do know that he was a scholar with a deep knowledge about ukiyo-e. In 1925, the business was moved to 20 West 46th Street.

The various moves occurred gradually northward, as the city expanded in the same direction.

Here are some links to pictures of E.T. Shima's businesses:

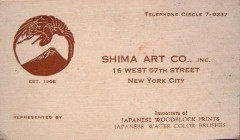

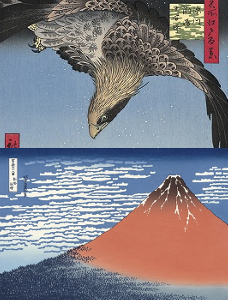

The Origin of the Shima Seal

Since the earliest days, the "Shima" seal was used as the logo of the company.

The Japanese word "shima" means island.

The kanji character above is an older representation of "shima", no longer in common usage.

It is a compound character, consisting of 2 other characters.

The right part is the Japanese character "tori", the word for "bird".

The left part is "yama", or "mountain".

The seal for the Shima Art Company consists of a very clever design, showing a bird over a mountain,

inspired by an eagle from Hiroshige along with Hokusai's masterpiece "Red Fuji".

The perfect logo for an ukiyo-e dealer named Shima!

Since the earliest days, the "Shima" seal was used as the logo of the company.

The Japanese word "shima" means island.

The kanji character above is an older representation of "shima", no longer in common usage.

It is a compound character, consisting of 2 other characters.

The right part is the Japanese character "tori", the word for "bird".

The left part is "yama", or "mountain".

The seal for the Shima Art Company consists of a very clever design, showing a bird over a mountain,

inspired by an eagle from Hiroshige along with Hokusai's masterpiece "Red Fuji".

The perfect logo for an ukiyo-e dealer named Shima!

2. Shima's marriage with Kazue Nakamatsu Kazue was born on December 13, 1894 in Ichinose village, Wakayama Prefecture, south of Osaka,

as an eldest daughter of 12 children of father Yoshinosuke Nakamatsu and mother Chika.

The Nakamatsu family was the village headman of Ichinose from generation to generation and they owned

quite a large rice field.

Kazue was born on December 13, 1894 in Ichinose village, Wakayama Prefecture, south of Osaka,

as an eldest daughter of 12 children of father Yoshinosuke Nakamatsu and mother Chika.

The Nakamatsu family was the village headman of Ichinose from generation to generation and they owned

quite a large rice field.

Although Kazue wanted to go to a teachers' college for women after graduation from the Tanabe Girls' High School as one of the first graduates of the new school, she decided not to do so because of the circumstance that a woman with a higher academic status might not be able to marry. So she stayed home, learning housekeeping and cooking after graduation. A marriage proposal with Torazo Shima, who was her uncle-in-law and was 17 years older, came to her. She had to study English conversation to live with Torazo, and she did it for about two years under a British woman in Kobe. Then, she married with Torazo at the age of 24 in June, 1918, and went to U.S.A. 3. The death of E. T. ShimaAt the shop in N.Y., there was an able manager, William (Billy) Lee Comerford, who carried out office processing, and the shop prospered. But, Torazo died of influenza pneumonia at the age of 49 in May, 1927. At first, Kazue thought that she had to close the store and go back to Japan. But she decided to stay there and keep the business, because Billy helped her. She lived with her girl friend and learned western-style dressmaking. She also taught a class of the art of Japanese tie-dyeing in summer semesters at the Columbia University, Teachers' College.4. About Hango Sumii Hango was born on October 1, 1893 in Takehara town, Hiroshima Prefecture, which was located in the east of Hiroshima City,

as a second son of father Toyokichi Sumii and mother Koyo.

Toyokichi's trade was a wholesale and retail of grocery, dried food, and rice, and he was doing business extensively.

Hango helped the trade, after graduating from the Takehara senior elementary school.

And he was drafted at the age of 20.

Because Hango was very honest and diligent and because he did his job in excellent performance, he was promoted to the

first class private in one year and released from duty, whereas the usual term of military service was for two years.

Then, elder brother Ryoichi, who had already emigrated to New York City, invited Hango and he landed on the West Coast by

formal visa, and arrived in NYC at the age of 23 in 1916.

Hango was born on October 1, 1893 in Takehara town, Hiroshima Prefecture, which was located in the east of Hiroshima City,

as a second son of father Toyokichi Sumii and mother Koyo.

Toyokichi's trade was a wholesale and retail of grocery, dried food, and rice, and he was doing business extensively.

Hango helped the trade, after graduating from the Takehara senior elementary school.

And he was drafted at the age of 20.

Because Hango was very honest and diligent and because he did his job in excellent performance, he was promoted to the

first class private in one year and released from duty, whereas the usual term of military service was for two years.

Then, elder brother Ryoichi, who had already emigrated to New York City, invited Hango and he landed on the West Coast by

formal visa, and arrived in NYC at the age of 23 in 1916.

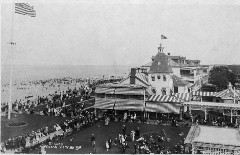

He made his living by helping his Japanese friend's souvenir shop which was on the beach of NYC suburb in summer. Because the souvenir shop was closed when summer had gone, he stayed in Y.M.C.A. of NYC while business was closed. Hango had a hard time with English at the beginning. He went to an elementary school in NYC. He could read English newspapers several years later. Then he became a house boy of the president of Yuban Coffee Co. during wintertime. He earned the master's thick confidence because of his industry and sincerity. It is thought that he learned remarkable manners at this time.

Here are some links to pictures of Hango's various businesses:

5. Kazue's marriage with Hango SumiiGoichi Takagaki, who was a cousin of Kazue, came to NYC as a NY branch manager of the Nomura Securities Co. In 1928, Takagaki introduced Kazue to Hango Sumii, who was successful in import business. When Kazue sat on a chair at a restaurant on the day when they first met, by Ladies first, Hango drew the chair and let her be seated. She had a very good impression of him and thought that he might become her better half. Although she could not decide to marry soon, by persuasion of Takagaki, she accepted the marriage. After taking the ashes of Torazo back to Japan, into the cemetery of the Shimas, Hango and Kazue were married on October 10, 1929 in NYC Japanese Church. In those days of Japan, it was uncommon for the son of a merchant and the daughter of a village headman to get married.6. Business after the marriage Once they were married, in order to be able to concentrate on the management of Kazue's hanga store,

Hango kept only two stores in Ocean View Park, after closing all the other stores.

Hango's hangers-on were asked to leave from the newly wedded home.

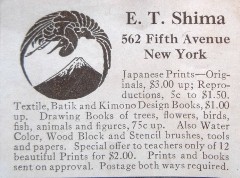

Hango ran the shop with the same trade name, "E. T. Shima", and moved it to 562 Fifth Avenue with the

capital obtained during the downsize of the shops.

Later, it became clear that it had been fortunate to have reduced the scale of stores.

Because, during the Great Depression, starting from October 24, 1929, the sale of hanga prints did not fall off.

Once they were married, in order to be able to concentrate on the management of Kazue's hanga store,

Hango kept only two stores in Ocean View Park, after closing all the other stores.

Hango's hangers-on were asked to leave from the newly wedded home.

Hango ran the shop with the same trade name, "E. T. Shima", and moved it to 562 Fifth Avenue with the

capital obtained during the downsize of the shops.

Later, it became clear that it had been fortunate to have reduced the scale of stores.

Because, during the Great Depression, starting from October 24, 1929, the sale of hanga prints did not fall off.

They distributed real ukiyo-e to universities and art museums around U.S.,

including an original Sharaku which was purchased by the Smithsonian Institution.

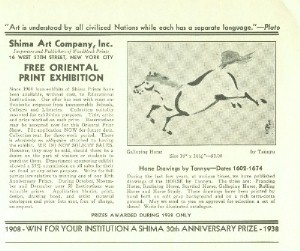

Shima Art Company spread its business not only dealing original and duplicated ukiyo-e, but also dealing shin-hanga prints which newly came out at that time. They dealt entire runs of shin-hanga prints from publishers such as Watanabe, Hasegawa, and Kawaguchi of Tokyo. Moreover, the Maruyama-Shijo school's kacho-e prints were bought in from Kyoto (maybe from Unsodo). Their efforts helped to make shin-hanga prints become popular in USA. However, when the supply from the publishers was inadequate, Shima committed to publish shin-hanga prints having their own seal imprinted and sold at lower prices. At least some of these prints were manufactured at Daikokuya of Tokyo. Shinnosuke Koizumi, who took over Daikokuya from the Matsuki family, collaborated with Shima, and they selected designs that would appeal to American taste. Another manufacturer of Shima's prints was the Daimaru Book Company, in Osaka. This information was uncovered by Robert Schaap, in his examination of Robert Muller's files. As for the price of shin-hanga in those days, the picture of newly-arrived Hasui's oban size print was sold at $5.00, and $7.50 - $15 for the older prints. The prints of Shima's own was sold at $3.00 for oban size, $1.25 for chuban size, and $0.50 for Christmas card size. Some links to printed catalogs:

Some links to other documents:

7. About the customersMrs. Anne Morrow Lindbergh was a customer of the store. It became a great sensation when her son was kidnapped and murdered. All the mass media wanted the scoop of her son's photograph. Since Mr. Sumii was reliable, she asked him to frame her son's picture which remained unpublished. She felt comfort by visiting the gallery and talking with the Sumiis.

8. Transfer the business to Mr. MullerIn late 1939 or early 1940, when the U.S.-Japan relationship had gotten worse, the Sumiis and Mr. Muller discussed the sale of the Shima Art Company to Mr. Muller, who planned to open his own gallery. The manager, William (Billy) Lee Comerford was to stay on, working for Mr. Muller and supplying him with all of the Sumiis' sources and connections. On February 3, 1940, Mr. Muller married with Ingeborg Lee, and they went to Japan and China for honeymoon trip. He bought many shin-hanga prints in Tokyo.Finally, in September, 1940, the Sumiis sold almost all the inventories of the Shima Art Company to Mr. Muller for $7,500. But they kept a very few prints for themselves. At this point, the history of the Shima Art Company was finished. In October, 1940, Robert Muller re-named the business as the Robert Lee Gallery, apparently a combination of his first name and Billy's middle name. When he heard about Pearl Harbor, he rushed to the store and removed all the enemy country's stuff from the wall and displayed common Western pictures. Soon the store was closed during the war. The relationship between Bob and Billy ended soon after that. 9. Beginning of the World War IIHango was so good-natured that, when Japanese diplomats came to Washington, D.C., he was asked to take them around Norfolk frequently. This became the reason why he was arrested for suspicion of being a spy on the day of Pearl Harbor (unlike Japanese on the West Coast, civilian Japanese on the East Coast were hardly put into the concentration camps). Hango was taken by FBI on the night of December 7, 1941. It was one week later that the family knew he was detained on Ellis Island. He was transported to Camp Upton in Long Island, NY, and then to the Fort George G. Meade, MD.The Sumiis were keeping a considerable amount of money in cash, which was received from Mr. Muller, for fear that if they deposited it in a bank, it might be confiscated by the government. Kazue had much trouble with hiding the cash in a house after the outbreak of war. Because if a woman of an enemy country kept a lot of cash, it would not be amazing for her to be suspected as a spy. Kazue hid it in bowls of foliage plant or canned foods. She helped many Japanese families with it, whose husbands were similarly arrested or had no jobs. One day, Kazue and Noriko, the only daughter of the Sumiis and my mother, made a trip to Maryland to meet Hango. At a moment when a guard soldier did not watch them, Kazue asked Hango in Japanese "What shall I do with that?", and Hango whispered, "Burn it!" But she could not burn the cash and kept it in hiding. 10. Leaving for JapanExchange ships were prepared by both governments in order to send diplomats back to their mother countries. Persons working for Japanese government, company, or bank, students with Japanese government scholarship, and their family were the main candidates to the ship. But, some civilians could also apply for passage. The Sumii family was appointed as returnees by the Japanese government and they decided to go back to Japan. At that time, Hango was 48, Kazue was 47, and Noriko was 11 years old. Bank deposits were frozen and confiscated by the U.S. government. Before leaving, Hango asked his most trusted American friend to take care of the cash and Mr. Muller became a witness. But he lost correspondence with the man during the war and after.On June 11, 1942, all returnees were gathered at the Pennsylvania Hotel and underwent very severe inspections. Each person was allowed to bring only 300 dollars and personal effects; the remainder of their possessions were confiscated. Several years later, after the war, the Sumiis' personal property, such as a professional Singer sewing machine and suitcases, were returned. They got on buses, which reached New York Harbor to board the ship, Gripsholm, which was of a neutral country, Sweden. They walked to the ship, while military policemen with bayonets were strictly watching them from both sides. Mr. Muller broke the policemen's line and came to meet the Sumii family, helping with their luggage. This was a very public statement of support for some friends who happened to be of a race and nationality which was both disliked and distrusted at the time. After all the passengers were onboard, the ship did not move soon because of political reasons. She was moored off of Staten Island for one week, and, on June 18, she shipped out of New York after some Japanese diplomats had boarded. The ship picked up the returnees from the South and Central America at Rio de Janeiro on July 2, and, via the Cape of Good Hope, it arrived at Lourenco Marques, Mozambique on July 20, which was the territory of a neutral country, Portugal. Then, the exchange of prisoners of war was performed. From Japan, the Asama-maru of Nippon Yusen Kaisha, Co. and the Conte Verde of an Italian ship arrived. The group from North America rode on the Asama-maru. Huge white crosses were decorated on the main deck and both sides of the ship, and were illuminated all night. For many days, the passengers had to carry their life jackets everywhere while the ships were crossing dangerous areas of floating torpedoes. The ships called at Singapore on the way, and finally arrived at Yokohama on August 20. 11. Life in JapanHango deposited his American money into the Yokohama Specie Bank which was the only exchange bank, where it was compulsorily converted, by national policy, into stock and bonds of various projects, for example the Manchuria Railroad Company Incorporated. All of those "investments" became worthless slips of paper after the war. Kazue often complained that: "When in the United States, we suffered troubles because we had money, and after our return to Japan, we suffered troubles because we lacked money".Because Hango returned to Japan by the national expense, he wanted to carry out a volunteer activity,

and he worked for the Takehara town public office, his hometown, without remuneration.

After the war, he worked as an interpreter for the chief officer of the Kure Police Station,

where a naval base existed, and mediated the relationship between the police and the U.S. Occupation

Forces for several years.

After that, he started a needle-making factory, but it went bankrupt.

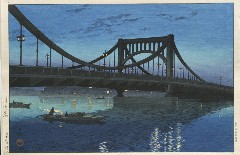

On May 8, 1948, Kawase Hasui visited Takehara and stayed at the Sumii's house as their guest.

There he designed the print Matoba, Takehara.

Also, he made a color sketch (seen to the right) for the Sumii's as a remembrance of his visit.

When Mr. Muller came to Japan for his business, he always dropped in at Hiroshima where Noriko's

family lives.

The courageous friendship displayed by Mr. Muller at the NY harbor deeply moved Takuro Tamaru, an orthopedist

who is Noriko's husband, and he always welcomed and invited Bob for trips around San-in, Kyushu,

and other places in the western part of Japan.

Hango dispersed his financial company in his 70s. He lived his fortunate later life, and died at the age of 88 on May 19, 1982. Kazue loved horticulture, composed haiku poems, and spent time communing with nature and God. After her husband's death, she lived in Hiroshima and Takehara, back and forth. She closed her long life of 95 years on January 24, 1990. They were pious Christians and did not miss weekly church worship. However, they followed the Japanese religious customs to respect their ancestors in Buddhist style. That is why they are sleeping in peace in the cemetery of Shouren-ji, the family temple, under the only grave with a cross. The author of this history, Dr. Kotaro Sumii, is both the grandson and the adopted son of Hango and Kazue Sumii. He was born the son of their daughter, Noriko, and her husband, Takuro Tamaru. Dr. Sumii is a physician and researcher, specializing in cardiology. His home is in Higashiku, Hiroshima, Japan. Dr. Sumii requests that anyone with further information about Shima Art Company please get in touch. Thank you, Sumii-san, for sharing with us the very interesting story of your grandparents' lives! |

|

| Home | Copyright 2004-2018 by Kotaro Sumii and Marc Kahn; All Rights Reserved |