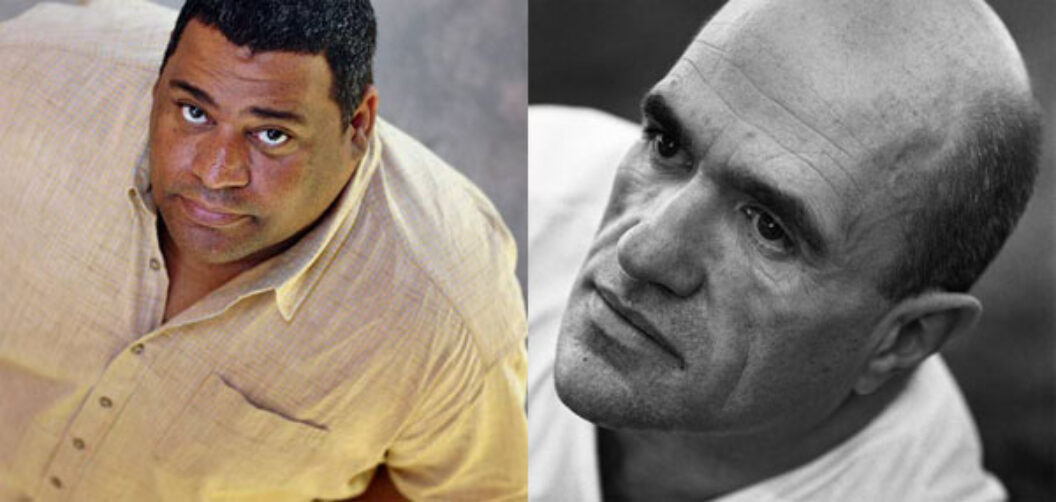

Christina García. Photo by Norma I. Quintana.

There are many things that can be said about Cristina García: That she is one of the most important Cuban American voices in US literature. That she was born in Havana but moved to New York City with her parents after Fidel Castro came to power. That she grew up in Queens, Brooklyn Heights, and Manhattan. That she has a Bachelor’s degree in Political Science from Barnard College, and a Master’s degree in International Relations from Johns Hopkins. That her first job was a marketing position with Procter and Gamble in West Germany, which she held for three months. That she has been a journalist for Time. That from 1990 onwards she has written fiction full-time.

Or one could talk about her gifted daughter Pilar. That she speaks Spanish to her daughter and her friends, believing that we will learn by osmosis, because life cannot be contained in one language, because beauty is too fluid for one tongue. It has been rumored that she sometimes has an uncomfortable relationship with Cubans, both on the island and in Miami because she has generally not engaged in anti-Castro activism. That she is a Cuban deeply embedded in the Salvadoran community. That she thinks there are many ways to be Cuban, and human and alive. That she is generous and giving and loving and paints, and dances and has a complicated and deeply beautiful spirituality. That she loves antique stores and thrifting and old style movies and the French Avant Garde. That her Cuban beans and rice and chicken taste like you’ve always imagined they should.

That in her new book, A Handbook to Luck, we meet three children: Enrique Florit, from Cuba, taking care of his flamboyant but often hapless magician father; Marta Claros, struggling in the slums of San Salvador, forced to leave school to help support her family; and Leila Rezvani, a wealthy surgeon’s daughter in Tehran, whose mother seems concerned only with appearances, and whose father is an out-spoken opponent of the Shah. We follow them over twenty-six years through intersections and near misses, through personal sacrifices and forced exiles, as Cristina weaves stories of tenderness, possibility, elegy and caretaking all of which culminate in a tale full of light, joy but also tragedy.

I can say all that, but mostly I want to say this:

Cristina García is my friend. That she teaches me every day how to carry history, memory and kindness with an easy grace. I want to say that she is a gifted writer who writes books that matter. I want to say she is a joy in this world.

Cristina García published Dreaming in Cuban, which was nominated for the National Book Award, followed by The Aguero Sisters, Monkey Hunting and now, A Handbook for Luck. She has been a Guggenheim Fellow, a Hodder Fellow at Princeton University, and is the recipient of the Whiting Writers Award.

Chris Abani In this new book, A Handbook to Luck, fate (or luck in this case) plays an important role in how the individuals in the narrative live out their lives. And yet this is not fatalistic. There is a fair amount of free will, even the employment of magic. Would you say that the three lives alternately play out the ideas of what is probable, possible, and inevitable?

Cristina García I think there’s a tremendous amount of tension between what’s probable, possible, and inevitable in this book. A density of suspense. Each of the characters, in his or her own way, battle the powerful undertow of what’s expected of them from their families and the larger society: Enrique in terms of his filial duty to his crazy magician father; Marta as a poor, uneducated woman from the slums of San Salvador; and Leila, as the privileged daughter of upper crust, pre-revolutionary Tehran. These expectations mark them, allow them a measure of florid suffering, but they also present myriad, twisted opportunities for change. I guess this just is another way of saying that I believe their fates, perhaps all our fates, remain somewhat flexible. Yet luck, coincidence, happenstance play a huge role. One wrong move might ruin potential bliss; a right one, invite it in for a spell. But nothing is taken for granted, or lasts very long. The contract is renewed every day.

CA Your characters here display an amazing grace under fire. Is this how you test their humanity? Or is this something you deeply believe about people—that we often behave surprisingly under pressure, and if we are lucky, we emerge having earned our deeper humanity?

CG We were joking the other night about some of the early reactions to your new novel, Virgin of the Flames, how crucial it is to traverse the grotesque in order to approach, even earn, the sublime. It’s a very Catholic idea, really, and we’ve both been duly inculcated with its magical thinking. In fact, the path to sainthood is a long detour through the grotesque! Think about our favorite saints and how they spent their lives—eating bee pollen, self-flagellating, avoiding sex, starving themselves on lonely mountain tops. So in a sense, yes, I do believe there’s something to the idea of personal crucibles, of emerging stronger from them (if you survive, of course), of exercising your free will to your very last breath. But the world isn’t a fair place, for the most part, and the earth is littered with the bodies of those who died trying. If we are extremely lucky, though, we do survive and grow and are the better for it. I think Marta, my Salvadoran character, is the closest embodiment of that in the novel.

CA Of all your books since Dreaming in Cuban, this new book is your most deeply, even rawly emotional. You take on difficult subjects, you follow the ways in which the female body is described and circumscribed by masculinity, but there are two elements here more developed: masculinity is brought under a new scrutiny and handled with a real tenderness, and the scope of the novel opens up to a more global perspective (charting Los Angeles, South America, and Iran). Do you feel freer now to open up more directly this way and to tackle all of your characters with equal depth?

CG Aren’t we all female impersonators in one way or another? That’s one of the things I loved so much about your new book: how you engage notions of gender and grace without the usual, tedious background noise. Men needing to become more like women; women needing to become more like men; everyone on the slippery continuum in-between. It’s powerful as hell.

I very much wanted, too, to explore the entrapments and trappings of gender in my novel. It would be easy, and overly simplistic to frame everything in terms of equality, or cultural limitations, or other vivid measurables. What’s most interesting to me are the slow, internal, often largely unconscious processes that move people in unexpected directions, that reframe and refine their own notions of who they are, sexually and otherwise. With the character of Enrique, for example, we see him at times tenderly, at times resentfully “mothering” his recalcitrant father. What could be closer to the heart of motherhood? Or the way he suffers heartbreak on more “feminine” terms?

I also wanted to break free of seeing the world largely through the eyes of Cubans or Cuban immigrants. After the first three novels—I think of them as a loose trilogy—I wanted to tackle a bigger canvas, more far-flung migrations, the fascinating work of constructing identity in an increasingly small and fractured world.

CA I love the humor in the book. The scene where Marta’s friend demands that her husband perform oral sex on her is hilarious, deeply moving and fiercely revolutionary all at the same time. Do you think there is something to being a transnational writer yourself, or in Cuban thought, that allows you to tackle subjects in this nuanced and complicated way so easily?

CG What?! Oral sex is complicated?! Okay, okay, I see what you’re getting at here. The key to your question is in the word perform. It’s all performance, don’t you think? The idea, as the poet Charles Wright recently put it, of giving illusion then taking it back. It doesn’t matter whether it’s a matador in the bullring, a writer at her desk, or someone giving or receiving oral sex. There’s no performance without fear, either. If a character could just as soon kill you as kiss you, that’s interesting. For me fear means moving toward darkness, into the half-hidden, the overlooked, the filched, the corrupted, the unknowable and coaxing it, however clumsily, toward language; language with the potential to score your tongue. And all the while respecting the music of silences. Now I’m sounding totally full of myself! Help me out here, Chris.

CA I am fascinated by your use of trees. In nearly every book you have written, there is a tree as refuge, as essential connection to a lost (or at least confused) mythical past, as cure, as portal for transformation. What is most interesting is that in your work, trees lose any singular reading, such as phallic symbol, and become instead the equivalent of the crossroads. Since in Christian, particularly Catholic ideas, the tree is the rivet of the sacrificed body (from Odin to Christ), what helps you remove it from sacrifice to redemption, to transformation?

CG I’ve loved trees ever since I was a little kid. The notion of something so huge living and growing on what seems like nothing is astonishing to me. Over Christmas, I finally drove up to the redwood forests in northern California, something I’d wanted to do forever. They took my breath away. There was this one huge tree, in particular, that some 1920s entrepreneur wanted to cut down and transform into an outdoor dance floor. Can you imagine? But it’s the American way, no? Cutting down our testigos, our witnesses, then turning them into profitable monuments.

Trees are essential to our survival, a form of prayer. The Buddha was enlightened under a peepul, or bo, tree and many other trees are sacred to Hindus and Buddhists. In Afro-Cuban culture, the ceiba tree is also sacred, a kind of maternal, healing figure to which offerings are made, petitions placed. So absolutely, for me trees do represent a crossroads, an opportunity for redemption and change. In Dreaming in Cuban, Pilar Puente has a transformative experience under an elm tree that leads to her returning to Cuba. Chen Pan, in Monkey Hunting, escapes the sugarcane plantation under the watchful protection of a ceiba tree. But it’s only recently that I’ve made trees protagonists in their own right. In A Handbook to Luck, Evaristo takes to living in trees as a young boy, to escape the violence of his stepfather. He stays there for years, first in a coral tree and then in a banyan. From his perches, he witnesses the greater violence of the civil war in El Salvador and speaks a peculiar poetry, born, in part, of his co-existence with trees.

CA Dreaming in Cuban employed a beautiful lyrical but almost dreamlike writing. Myth was much more on the surface. In subsequent novels, the voice has grown no less lyrical, but there has been a marked shift to more realism, a more concrete reality. Is this the movement on one level of the artist from finding a voice to claiming it? Or is it actually a function of the stories you tell?

CG I think it’s true—and I miss my magical realism! Although there are still elements of magic and otherworldliness in my work, things difficult to explain rationally, I’ve been more drawn to the border between what is remotely possible and what is quite impossible (although there isn’t much for me that falls irrevocably in that camp). In other words, I ask myself: Given the right—even rarefied—conditions, could this actually happen? It’s a line I’ve seen you walk in your own work to mesmerizing effect. The purely magical seems a bit easy to me. I’ve set myself to earning these moments more, embroidering my way to points more ambiguous than surreal. There’s a funeral scene in A Handbook to Luck where I explore this most fully. Did my megalomaniac magician, Fernando Florit, pre-arrange the dazzling pyrotechnics at his funeral, or was he somehow orchestrating them from the dead? The real magic to writing, I think, is resisting predetermined outcomes.

CA The archetypes and symbols you use repeatedly in your work are mixed; drawn from different cultures and traditions—Christian, Yoruba, Carob, Cuban and Classical. As you know, I am all for this kind of mixing, of the idea that there is no text without intertext, the idea that all cultures and myths are in dialogue with each other. In Nigeria this is seen on prayer mats, the painted signs on lorries and so forth. It seems to have permeated the day-to-day of culture, and yet is often resisted by literary writers who seem to subscribe to a sort of purity of idea. Where do you stand with regard to the hybrid, the mongrel?

CG Viva el mongrel! These days, anything else seems more wishful thinking (or newsreel-y nostalgia) than truthful. It’s exciting and dangerous and less predictable, but where else would you want to be? It’s up to us, as writers, to transform the violence and cultural upheaval and migrations all around us into stories and syntax that reflect and illuminate these new realities, distort them gorgeously. To me, good fiction is about disproportion. As much as I still love to listen to a Bach chorale, I’m personally more drawn to the messy dissonances of contemporary music.

CA I know writers hate this next question (I know that I do), but having been fascinated by your characters in every book, I want to know how you draw them? Do they come from life, do you completely invent them, do they direct the story or is it a conversation between them, both changing each other alternately, as in life? And I ask this knowing the tendency of mainstream culture to make the “other” body occupy the real while allowing the “mainstream” body to fully occupy the imagined.

CG Speaking of bodies, to me creating characters has everything to do with the flesh. Inhabiting their flesh, feeling the rush of blood in their veins, the electricity of their panic attacks, their ecstasies, their indigestions. I think of it, to borrow a phrase from Víctor Hernandez Cruz, as a collaboration between survival and creativity. There’s the work of survival, which means making sure the characters eat, sleep, work, and fornicate convincingly, that they’re alive to me as a real person might be. In that regard I’ve borrowed liberally from life and people I know, not wholesale but piecemeal: a manner of speaking here; the arch of brow there; something essential about their outlook or sense of melodrama (I have plenty to draw from in this department within my own family). But from there, the fun task of departures and encrustations begins. For me it’s far less interesting to remember than to interpret. Rarely do the final realized characters have anything to do with the increasingly obscure people who inspired them. Yet there are other characters—Chen Pan in Monkey Hunting, for example, or Ignacio Agüero in The Agüero Sisters—who come to me not from my own life but little by little, as gifts from history and poetry. What they all have in common is this: they are born of my obsession and pleasure.

CA One of the most interesting things about your work is how you deal with the idea of displacement—national, cultural, mythical and even on some level, narratively. You seem to work not only with the idea of the liminal or the ambiguous, but also with the idea of multiplicities. That said, when you begin to write, is it as much a journey of discovery for you as it is for the reader later, and also, are you ever disturbed and uncomfortable with what you find on the journey?

CG Yes, I’m constantly sending tap roots into all sorts of unsavory places. That’s an essential part of the mystery and discovery for me. I expect to be disturbed. I hope to be discomfited. I want to be derailed from my suppositions. A lot happens before I even attempt to write the first word of a new novel. For me, it always begins with obsession. I start circling particular subject matter or terrains, reading voraciously, giving myself over to these interests. Last summer, I spent most of my waking hours reading about bullfighting and the civil war in Guatemala. I immerse myself in the bigger themes and from them, specific characters emerge. The displacement comes from navigating so many borders—personal, cultural, narratively, mythically—that are perforating, shifting unpredictably. That is why I use a multiplicity of voices to tell my stories. I don’t trust (purported) omniscience, authorial or otherwise.

CA You have a magician in this book and a character who lives in trees. Is it wrong to assume that these devices, the very form of your storytelling relates to Eshu? Eshu being the Yoruba god of the crossroads, a trickster who reveals and conceals alternately, but who is the only one who speaks all languages and so while he is not to be trusted, the gods require him for communication with each other. Do you think that at some level, your writing does this? Leads to revelation and epiphany with small cumulative moments rather than the direct linear narrative plot that the American novel of recent years does? That at some level, language itself is the subject of some of your work and that it reveals and conceals simultaneously, particularly in this new book. I am thinking of the direct and indirect employment of magic and a form badly alluded to as magical realism.

CG Wow—you nailed that one! I’ve been fascinated by the Eshu figure since writing Dreaming in Cuban, only that in Afro-Cuban culture he metamorphoses into Elleguá, the god who must be placated first, the messenger to the other orishas, the essence of potentiality, the only one who knows the past, present, and future. For many years, I kept a small altar in my office dedicated to Elleguá, with a little statue of him I had made and blessed in Cuba. I offered him rum, cigars, toys, fruit (I couldn’t quite bring myself to sacrificing a rooster or he-goat, his preferred propitiations). Elleguá’s vision surpasses that of the other gods yet he is often mischievous, a prankster, an eternal child. As an archetype, he is opportunity, chance, the unexpected. I want everything Elleguá represents to be reflected in my work. I can only hope that the lucky gifts of language and incidence that sometimes occur are due, in part, to magical intervention.

CA Being a writer is an odd thing because it often means that you have to be silent for the work to emerge. A sort of screaming without sound as Marguerite Duras puts it. Do you think there is something inherently contradictory about being a writer? That we have to live in the real and the imagined simultaneously and yet often are unable to render both meaningfully.

CG There are at least three realities competing for my attention at all times: the world I’m writing; the world I’m reading; and the world of my daily life (frequently the least interesting!). Each world tugs on me relentlessly and I’m rarely, if ever, able to do any of them justice. To me, nirvana would be to live all these worlds fully, in color, during a long radiant season. But there are disagreeable places they put people in who try to do things like that.

CA What is your process?

CG After the pre-novel saturation I described earlier, I surround myself with poetry books, a shifting array of them. Before I begin a writing day, I will immerse myself in them for an hour or two. Somewhere in that process, if you can call it that, I’ll randomly stumble across an idea, a fragment of language, a single word that will lead me to that day’s work. It’s that unpredictable, at least in writing my early drafts. Poetry is my daily bread.

CA If you could say something to your readers, what would it be?

CG To borrow a song title from Gypsy (that crazy burlesque stripper): “Let me entertain you.”

CA What are you writing now?

CG I’m currently working on a book tentatively titled “The Lady Matador’s Hotel.” It’s set, for the most part, in a luxury hotel in Guatemala City ten years after the end of the civil war. One of the main characters is a Mexican-Japanese matadora, in town for an all-female bullfighting competition. Everyone in the novel is as displaced as she is: a Korean textiles manufacturer; an ex-guerrilla now working as a waitress in the hotel coffee shop; a Cuban poet who’s come with his wife to adopt a daughter in Guatemala. No one truly belongs, yet they’re co-habiting this Westernized space and negotiating like mad to make sense of their circumstances.

CA Finally, in the spirit of those great American Express Card ads, what is your passion, as Cristina?

CG Doing interviews with you!