In the beginning, in Italy, there was the osteria. And you had to bring your own food.

Relatively recent are the osterie we know and love today–those places where, whether for a solo lunch or for dinner with friends, tables are laid full of food and wine. Places where, in Tuscany for example, you might find hefty cuts of bistecca alla fiorentina and long strands of pappardelle coated in wild boar ragù. Or, in Puglia, orecchiette with biting cime di rapa and pesce al forno, caught just that morning by the local fisherman.

Almost 3,000 years ago, the mere idea that you could be served food outside of the home–let alone this level of culinary expertise and abundance–was unimaginable. The primary function of the osteria (the firsts of which appeared between the 7th and 8th centuries), today what we would consider more of an inn, was rather room and board for travelers. They were spots where the main focus was wine, the scent of which rose from the wood of the tables, and a few cold accompanying dishes–hard-boiled eggs, cod fritters or slivers of parmesan cheese. To ask for a bottle, all you had to do was shout “WINE!”

If, and only if, the tavern had a kitchen, then simple dishes could also be found, reheated there and then. Usually, it was the guests themselves–at this point, exclusively travelers or workers–who were expected to bring alimentation with them in a cartoccio or gavetta [workers’ lunch boxes]. This is still the case, for example, at one of the oldest taverns in Europe: the Osteria del Sole in Bologna’s Vicolo Ranocchi. Since 1465, in the city’s historic center a stone’s throw from Piazza Maggiore, a sign simply promises “vino”. (Don’t miss the little garden, where you can still see the rings used for tying up horses.) Bologna, as today, was a capital of food in Italy: by the 14th century, there were already more than 150 osterias in the red-bricked city.

Over the years, some osterie–especially those close to mines, gravel pits or construction sites–began to serve “cooked” dishes and to bear the sign “Osteria con Cucina”. Tables were tablecloth-less and wooden, and for some bizarre reason, fruit was absolutely banned. The atmosphere was that of the average people–a place for joking, amusement and the occasional celebration of a festival or wedding.

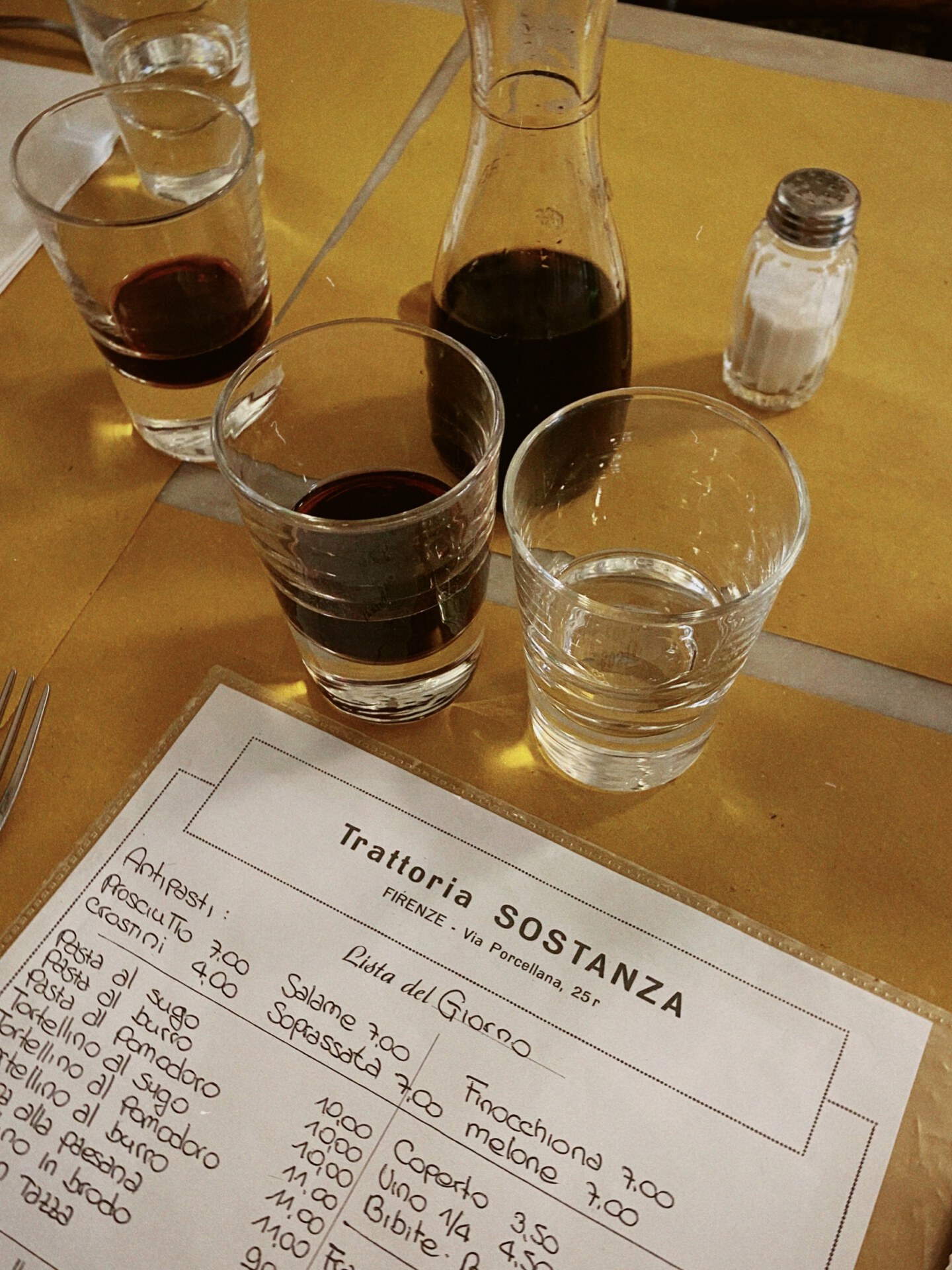

From this concept, osterias spawned hundreds of “trattorias”, taverns equipped, this time always, with a kitchen. Here, the primary function was the preparation of complete meals of regional cuisine thanks to unwritten recipes (especially from grandmothers and mothers), handed down in memory of the generations before and through which everyone had their own distinct way of cooking. It was a time when osterias and trattorias were primarily frequented by men, and women had limited independence and opportunities for work. However, as these establishments were family businesses (and the owner’s dwellings were usually on the floor above the eatery), women were able to intertwine family care and garden work with responsibilities as cooks and innkeepers. Women could therefore often be found in the kitchen: these were the places you could find homemade fresh pasta, the kind you roll out with a pin made strictly of wood, or broth made with meat and mashed potatoes from the garden, or even fried food made with two fingers of oil in old iron pans.

Yet, it was not enough, because the middle class liked to set a tone and thus restaurants were born. Until the late 18th century, elites regarded public spaces as dirty and dangerous and preferred to eat at home, enjoying the luxury of having a staff that cooked and cleaned just for them. As the middle class grew and capitalism accelerated, those same places were transformed into eateries for public relations and cultural experiences–places to see and be seen.

Ristorante derives from the French homonym restaurant and the Latin of “to refresh”. At the end of the 18th century, the first place that bore this name was born in Paris and served exclusively “the food that refreshes”: soup. Thanks to its proximity to France, Piedmont was the first Italian region with “proper” ristoranti. (The first restaurant in Italy may be Turin’s Il Cambio–a historical venue born in 1765 as an evolution of a primary café, a place where prominent people met to talk about ideas and politics.)

These new restaurants were equipped with menus, a kitchen brigade and well-separated tables–a far cry from the bare, noisy, communal-tabled osterias (not to mention menuless and seasonal–how cheap!). The formula included the services of the old osterias and trattorias, but with some extra care for the bourgeois class who felt safe with standardized menus, complete and mostly fixed à la carte, served at tables set by professional waiters. The list of dishes, unlike that of the trattorias which mainly offered local and regional foods, could also include more “exotic” indulgences and innovative recipes. Italians went to the ristorante, therefore, to taste and then gossip about special dishes, different from the typical homemade ones, and to eat fruit, but not in season (how luxurious!), and to drink whole bottles of wine, saying goodbye to the bulk variety.

But what remains of these distinctions today besides an etymological evolution? In Italy, there is a healthy and legitimate confusion. There are ristoranti with rude waiters, where the guest does not feel at all welcome, and Michelin-starred osterias (like the most famous in Italy, Osteria Francescana), dark kitchens without a restaurant and restaurants without waiters.

And if some nostalgic people say that the places of the past are increasingly disappearing–those where the truth translates into a well-made dish, cooked by expert hands like that of a nonna–then perhaps it is because dreams and imagination are lacking or perhaps because they haven’t been to Italy yet. We’ve still got them all: osterias, trattorias and ristoranti.