Art Fairs

Homegrown Talent Takes Center Stage at Artbo, Colombia’s Premier Art Fair in Bogotá

At the fair and beyond, galleries focused on celebrating Colombian artists.

At the fair and beyond, galleries focused on celebrating Colombian artists.

by

William Van Meter

One dress really stood out at last week’s Artbo, Colombia’s principle art fair in Bogotá. The hot-pink and safety-orange behemoth frock was a 32-foot-tall sculpture by the Swiss-Colombian experimental artist duo Mapa Teatro. It was suspended by wires from the ceiling of the Agora convention center, as fan-powered metallic streamers billowed from its sleeves.

The brother-and-sister pair of Heidi and Rolf Abderhalden worked on the site-specific installation with the Colombian architect Simón Hosie. Their sibling, Elizabeth Abderhalden, collaborated on the month-long tailoring of the tulle and silk portion, with three local seamstresses. Beneath the suspended artwork was a temporary theater, its floor littered with shiny confetti, where a video component of the larger “The Holy Innocents” (2011) project played.

At first glance, the installation looked like high-art Drag Race hijinks, but something more ritualistic was afoot. The project documented the annual Los Santos Innocentes celebration in the Colombian Pacific region, where masked men don women’s clothes and whip those found without masks.

Mapa Teatro’s audacious gown welcomes the VIP crowd on November 22. Courtesy of Artbo.

What looked like a party dress was actually a Trojan horse for something much heavier, a vibe that encapsulates both Artbo and the city’s broader art week. While other global art fairs are largely privatized events, Artbo is a product of the city’s chamber of commerce. There were no mounds of sponsored luxury purses to sidestep on the way to booths, or brand activation photo-ops, or blue-chip masterworks that were shipped in that you could guess the price of. Instagram influencers were MIA.

But Artbo’s divergence from the norm were its strengths. Whereas the experience of visiting other fairs can become a monotonous blur—a big box store of art packed up and shipped from country to country—Artbo’s focus, particularly this year, was on contemporary Latin American art. Traditionally, about 70 galleries participate. But for the 19th edition, the post-pandemic number has downsized to 33, with about two thirds of those hailing from Colombia and exhibiting mostly homegrown rosters with justified pride. Other countries represented included Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Spain. Artbo is the second largest art fair in Latin America after Mexico City’s global hub Zona Maco. There was a lot of talent on display.

An installation view of Artbo’s “Referentes” section. Courtesy of Artbo.

Content-wise, there was a lack of gender or sexuality explorations (or much nudity for that matter), street art, or graffiti. There were no robots anywhere. There was a lot of textile art and work that dug deep into history. It was all very adult and sophisticated, and a lot of what stood out was political. “Colombia’s tragic history lends itself poetically to art,” said the fair’s director, Maria Paz Gaviria. This could manifest as either confrontational or allegorical, especially when veering into the environmental. There was also a noticeable representation of indigenous artists and work that dealt with indigenous people’s themes.

At Instituto de Visión’s booth modern techniques were astutely employed in indigenous representation. The French-Colombian artist Karen Paulina Biswell wielded fashion photography tropes, while the Mexican artist Tania Candiani documented “The Danza de los Negritos,” an indigenous interpretation of an ancient African healing rite in a hypnotic video piece.

Karen Paulina Biswell, Kima, union, love, (2013) (L) and a still from Tania Candiani, Sanes de la Sanación (2022) (R). Courtesy of Instituto de Visión

Mapa Teatro’s “The Holy Innocents” was streamlined (perhaps more effectively) into a grid of stills with an accompanying streamer-adorned floor fan at Rolf Art, the artists’ Buenos Aires gallery. Its booth was a fair standout and a bastion of clarion protest. The multidisciplinary Argentine artist Gabriela Golder’s “Arrancar Los Ojos” or “Tear Out the Eyes” (2023), a heavily researched film, video, and sculpture project, was boiled down to a glimpse of black and white photographs. Golder’s work documents the widespread police tactic of purposefully maiming and blinding protestors with projectiles and gas. The stormtroopers were universal, it was hard to tell them apart from country to country.

Gabriela Golder, Arrancar los ojos (2023), video still

“I started this project in 2019 because I saw this terrible image of Chile when the police shot into the eyes of people,” said Golder, who was on hand. “They had more than 500 victims. Then I realized that this repressive method is systemic. It started in the 1970s in the Palestine-Israel conflict, and then it spread and [became more] sophisticated. It happened in Colombia, Hong Kong, France, Lebanon, Ecuador, and Barcelona.” She explained that her project was about vision and memory. “Oftentimes, when victims of violence lose one or both eyes,” Golder said, “then they say they can see more. They’ve ‘woken up’ and have sight.”

An installation view of Gabriela Golder’s “Arrancar Los Ojos”. Courtesy of Fragmento.

Golder’s intense, multi-pronged project could be seen in full glory at her solo exhibition which closed the final day of Bogotá art week at Fragmentos. The gallery doubles as Doris Salcedo’s monument to the Peace Accord signed between the Colombian Government and the FACR-EP guerrillas—its floor composed from 37 tons of melted weaponry, patterned and hand-hammered by sexual assault survivors from various militia groups.

Unflinching looks at oppression and its ramifications were balanced by Artbo’s third-floor “Referentes” section and it’s uplifting sense of rebirth. Guest curator Julieta González was tasked with assembling a room culled from the main floor galleries’ collections and delivered an enlightening, cohesive group exhibition. “This is basically a compendium of my interests for the past decade,” she said, “especially ecology, indigenous art, and those intersections. I chose to make it very Colombian and focused on recent aspects of Colombian art history.”

Jose Ismael Manco, Sicaramad (2019). Courtesy of Espacio El Dorado.

Some featured artists were previously unfamiliar to Gonzalez, such as José Ismael Manco whose charcoal drawing, Sicaramad (2019), of a human-buck deity, presided over a section with a spiritual undercurrent. José Alejandro Restrepo’s drawings were framed with dried samples of different hallucinogenic plants. “That section has to do with indigenous cosmovision,” Gonzalez explained.

“It was a way to look away from the necropolitic,” Gonzalez added, “to really think about the cosmopolitan and this entrance of nature into the political realm. What could this mean in terms of solving problems? So, it was a forward-looking and future-looking exhibition. Also, these indigenous societies that inhabit the territory are having more visibility, which also helps in the fact that they can secure more autonomy, to secure their livelihoods and their land.”

Nohemí Pérez, Un lugar en Orito (2023). Courtesy of Instituto de Vision.

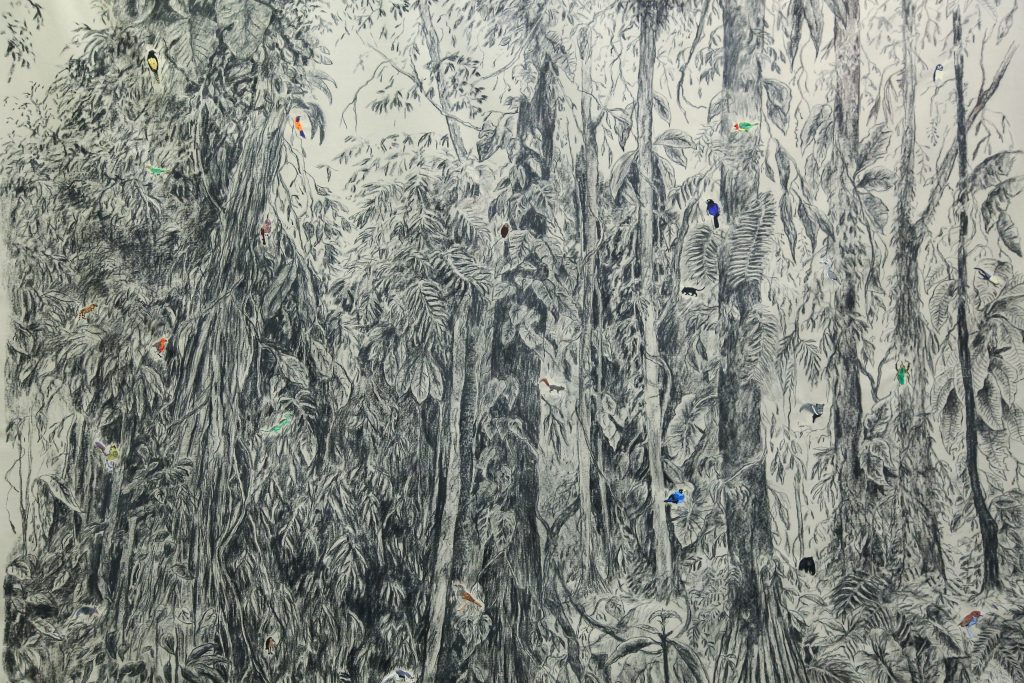

Nohemí Pérez’s large charcoal drawing of a forest appears to be a black and white depiction. But when you get closer and zero in, intricately embroidered colorful birds, beetles, and panthers abound. “Nohemí’s landscapes are important because in many cases they no longer exist,” Gonzalez said. “They’ve been destroyed by extraction. She’s from Catatumbo in Colombia, this region has been contested territory historically. There were coffee plantations, sugar plantations, a lot of monocultures.”

A detail image of an embroidered bird on Nohemí Pérez’s Un lugar en Orito. Courtesy of Artbo.

Agriculture was a theme throughout many works, with a lot of potato and corn-centric art. In all cases it had deeper meanings than still-life vegetation, the history of corn intertwined with the history of the ancient cultures. At Espacio Continuo’s booth, Juliana Góngora’s breast-like vessels Ofrendatarios (2021) were hung with rope and filled with kernels. The Colombian artist often wields the medium with grace. Eduard Moreno exquisitely oil painted a truck tarp with a vivid wreath of maize. Gonzalez installed Maria Elvira Escallon’s oversized-yet-realistic ceramic cob on top of a slab of cinderblocks.

An installation view of Artbo’s “Referentes” section. María Elvira Escallón’s Mazorcas is in the foreground. Courtesy of Artbo.

At the Galeria La Cometa visitors walked through towering cornstalks in burlap sacks as part of Carlos Castro’s “La Reste de Las Partes” show. “This plant is so important,” the Colombian artist said. “Before the conquistadors came here, corn was a currency and people would trade with it,” Carlos said, as he picked up a cob made of gold-plated human teeth (he sources them from Tijuana dentists). “We don’t know how much of the corn that we consume right now is real corn. Because it’s Monsanto and all genetically altered.” Castro also made a corn snake, brass knuckles, and filled popcorn bags with teeth. “Each of those teeth has the history of a person,” he said.

At Artbo, a mysterious shrouded kiosk was home to Ernesto Restrepo Morillo’s golden potato jewelry and creations. The artist has been working with potatoes since 1992. He was originally inspired as a response to the 500 year anniversary of the “discovery” of the Americas. “For him, potatoes were the maximum expression of Latin American identity,” his gallerist Steven Guberek of the Bogotá-based SGR Galería said, “and the clearest way in which Latin America colonized Europe.”

An installation view of Colectivo Mangle’s “Space, Limit of Absence.” Courtesy of SGR Galeria.

Upstairs at SGR’s home base, the Colombian carpenter-artist duo Colectivo Mangle (made up of married couple María Paula Alvarez and Diego Álvarez) presented suspended sculptures. The pair met while studying carpentry and decided to turn the practice on its head. Their sculptures resembled textiles but are made from bending solid wood pieces into graceful forms through a painstaking process of laminating, vacuum sealing, and chemical treating. Hovering poetically and phantom-like over the concrete floor, they remain floating in one’s memory.

More Trending Stories:

How an Exclusive NYC Cult Influenced the 1970’s Art Scene

A Rare Soulages Lithograph Possibly Worth $30,000 Sells For $130 in Facebook Marketplace Mishap

Masterpiece or Hot Mess? Here Are 7 Bad Paintings by Famous Artists

Is There a Hat Better Than Napoleon’s? We Rank Art History’s 5 Most Iconic Chapeaux