The tension and challenge of Passover this year

Rabbi James Prosnit

Jewish Chaplain, Campus Ministry

As the Festival of Passover draws to a close early next week, Jews around the globe will have had a chance to rejoice in the annual celebration of redemption and freedom, even as they reflect on the harshness and realities of the past year.

Seder tables are a place of inter-generational joy. Young children get to ask timeless questions about the rituals, and elders respond with words acknowledging the history of survival, and tenacity that has been central to the Jewish faith and experience. But the telling of the Passover story has a universal and timeless dynamic as well. We are reminded that in every generation there are the hungry and downtrodden, and we are God’s partner in responding to the pain of all of God’s children. While we may rejoice at oppression overcome in ancient days, we acknowledge the numerous plagues and ills still affecting God’s world today.

Some families left an empty chair at the seder table reflecting the 130 hostages still held in captivity by Hamas. Some families included readings reflecting the pain of those in Gaza or the Ukraine whose lives have been shattered by the current wars.

One ritual of the seder has participants removing drops from a cup of wine (symbol of joy), thereby lessening and diminishing our joy due to the suffering of others.

The following poem by Rabbi Margaret Frisch Klein captures some of the tension and challenge of Passover this year.

My creatures are drowning…

Why are you singing?

A drop of wine

A drop of blood

Not just 10 for the plagues

Too many drops to count this year

Maybe every year

A drop of wine

A drop of blood

We rejoice with each hostage freed

Out of the narrow places

A drop of wine

A drop of blood

A tunnel is a narrow place

A very narrow place

We weep for each life lost

Child, woman, man

Every Gazan, Every Israeli

Every soldier

Every “non-combatant”

Every victim from any country

Every person

Each created in the image of the Divine

A drop of wine

A drop of blood

We weep for each victim

Each victim of terror

Each victim of sexual assault

Each victim of displacement

Each victim of brutality

Each victim of promises made

And promises shattered

Each victim searching for water

And searching for food

And searching for safety

Searching for school

And searching for healing

Each victim of fear

We pray that soon

All will be out of the tunnels

Out of the narrow places

God admonished the angels

“My creatures are drowning, and you rejoice?”

A drop of wine

A drop of blood

Too, too many drops this year

We cannot sing this year

Next year may all be free

Out of the narrow places.

May this season of renewal, bring peace and well-being to all.

The Lived in Interior — Living a sustainable lifestyle

Hollie Sutherland, NCIDQ, LEED AP, MFA Interior Design

Assistant Professor, Interior Design

Interior Designer, Hollis Interiors

What is it sustainability and why should you care? Let me offer my perspective as a residential interior designer with experience both practicing and teaching the profession of interior design with a focus on sustainability.

Sustainability is good for your health. It touches your life and contributes to your health and wellbeing—the air you breathe, how you live in your home, and the materials you use, reuse or discard. These ideas evolved the definition of a sustainable building beyond energy and water efficiency. There is a richness and progression of the definition of sustainability that brings us to the idea of a sustainable lifestyle.

Here is a quick guide to the evolution of sustainability:

- Late 19th century: Preserve natural habitats. Activist, preservationist, and founder of the Sierra Club 1892, John Muir understood humans place in the natural world, and that we are a part of nature, not above it.

- Mid-20th century: Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), a sustainable building approach, focused on preserving natural resources and building smarter.

- Early 21st century: William McDonough, author of Cradle to Cradle, refers to nature, a perfect system. It teaches us how to design products emulating the life cycle of nature and eliminating waste.

- Mid-21st century: Two new sustainable building systems evolve, adding a humanistic perspective to sustainable design.

Three rating systems provide a blueprint for a sustainable building. In addition to LEED, there is the Well Building Standard and Living Building Challenge. New concepts such as attention to nutrition, growing your own food, exercise, access to nature and daylight, awareness of mental health issues and living in a sustainably built home, are all addressed in a sustainable lifestyle. These ideas influence designed spaces. A fundamental question is “How do you want to live in your home, and what does that look like and feel like to improve your health and wellbeing?”

In my view, sustainability is a lifestyle. Views to nature, a home gym or yoga space, access to daylight, a bed mattress made without chemicals, eliminating VOC materials (without harmful chemical content), repurposing materials such as antiques, eating healthy food or using materials that are certified sustainable—even your cleaning products—are all strategies applied to creating a sustainable home or building. A step beyond the original purpose of the LEED sustainable building approach—using the principles of the sustainable rating systems, the way you design and experience your home, can improve your comfort and contribute to your health.

To learn more about sustainability, consider reading about the Living Building Challenge and Well Building Standard, the two new sustainable building resources with a humanistic perspective. Additionally, Biophilic Design is a discipline that teaches how to bring nature into our homes in physical and interpretive ways.

To get started, do a complete critical analysis of your home and list everything that does not support your health, and in fact causes stress.

Recommended reading: Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things, (2002) by William McDonough and Michael Braungart. Also, Nature Inside: A Biophilic Design Guide (Browning & Ryan, 2020), and 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design, Improving Health and Well-Being in the Built Environment. Annette Stelmack’s Sustainable Residential Interiors is also a one stop book for a sustainable education. Wherever you start, it is worth your time to establish a sustainable lifestyle, and create a home that not only supports your health, but also the environment.

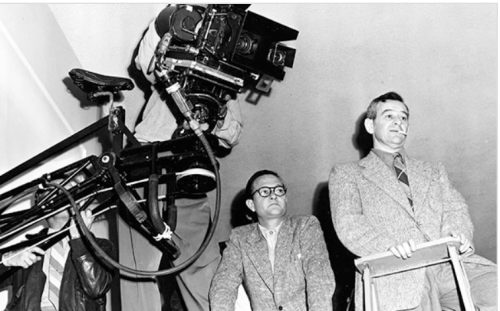

William Wyler: A Master Filmmaker Revisited

By Jay Rozgonyi

Associate Vice Provost for Pedagogical Innovation & Effectiveness

Director, Center for Academic Excellence

Instructor of both Educational Technology and Film Studies

How about this for a great Final Jeopardy question under the category The Oscars: “He’s the Hollywood director with the most Best Director nominations (12), the most Best Picture nominations (13), and the most acting nominations in his films (36).” Pretty good, I’d say. But chances are that the question will never be used—not because I’m not a staff writer for the show, but also because the answer would likely be considered too hard for most contestants, even serious film fans.

That they wouldn’t be able to name William Wyler is unfortunate, as he was one of the truly great filmmakers of the 20th century. A lot of his movies are well known: Wuthering Heights, Ben-Hur, Roman Holiday, Mrs. Miniver, The Best Years of Our Lives, Funny Girl… I could go on and on. But unlike Alfred Hitchcock and suspense, or John Ford and Westerns, Wyler didn’t focus on a particular genre; instead—as the list of films I just mentioned demonstrates—he moved from comedy to drama to romance to historical epic. Because of that, he was brushed aside by the critics of the 1960s and 1970s, who considered him a gifted Hollywood studio director but thought that he lacked a coherent artistic vision. In fact, Wyler’s highly diverse output was the result of a quest for innovation and a desire to challenge himself by always trying something new throughout a career that lasted nearly 50 years.

If you Google William Wyler filmmaking style, you’ll learn about the way he carefully composed his shots, staggered his actors from deep in the frame to extremely close up, and staged dialogue scenes with few cuts so all the characters are visible at the same time—all directorial techniques that demonstrate his meticulous craftsmanship. I see another element to his films, however, which hasn’t received much attention at all: a steadfast attention to social justice and basic human morality. Once you look for these themes, it’s as easy to spot as his striking camera setups and his precise use of light and shadow. Wyler’s firm sense of conscience comes out in the nuances of his stories and the characters who inhabit them, and in the subtle ways they speak to the issues of their respective days. We see it in 1937’s Dead End, where the Depression has left families broken and juveniles with little sense of hope for their future. We see it in 1946’s The Best Years of Our Lives, where GIs returning from World War II confront a home front that seems to have moved beyond them and their sacrifices, and toward a future focused on making money and assailing anyone who might be a “Commie.” And we see it in 1970’s The Liberation of L.B. Jones, Wyler’s last film and in many ways his most courageous—a brutally honest look at racism in America and the dehumanization it brings upon us all.

Over the course of 2024, Fairfield University is celebrating the career of William Wyler with an undergraduate course devoted to his work, a series of film screenings at the Fairfield Bookstore on the Post Road, and an exhibition of materials from his private collection titled William Wyler: Master Filmmaker, Man of Conscience, which will be on display at the DiMenna-Nyselius Library from September through December. We’re just a few years away from the 125th anniversary of Wyler’s birth in 1902, so this seems like a good time for a lot more people to get acquainted with the man and his films. Then, perhaps, by 2027, the Final Jeopardyanswer might even be too easy for contestants to ponder. Wouldn’t that be nice?

Fairfield University’s celebration of the life and work of William Wyler would not be possible without the generous support of his daughters, Catherine and Melanie Wyler. We thank them for all that they’ve done to enable us to share their father’s work with our community.

The following movie screenings will be open to the public at 6:30 p.m. on these dates at the Fairfield University Downtown Bookstore, located at 1499 Post Road, Fairfield, Conn.:

- April 9: The Best Years of Our Lives (1946); guests: Melanie Wyler (in person) and Catherine Wyler (via Zoom).

- October 1: The Desperate Hours (1955); guests: Melanie Wyler (in person) and Catherine Wyler (via Zoom); other Wyler family members may attend via Zoom.

- November 19: The Liberation of L.B. Jones(1970); guests: Melanie Wyler (in person) and Catherine Wyler (via Zoom); other Wyler family members may attend via Zoom.

Stephen Wilkes, “Easter Mass, Vatican City, Rome, Italy, Day to Night"

Stephen Wilkes (American, b.1957), "Easter Mass, Vatican City, Rome, Italy, Day to Night,” 2016 Digital C-print, Edition: 2, 48 x 111.5.

Through a collaboration between Fairfield University Art Museum and the Office of the President, photographer Stephen Wilkes’ large-scale work “Easter Mass, Vatican City, Rome, Italy, Day to Night” is on view at the Barone Campus Center.

Since opening his studio in New York City in 1983 Stephen Wilkes (American, b. 1957) has built an unprecedented body of work and a reputation as one of America’s most iconic photographers, and a National Geographic Explorer, widely recognized for his fine art, editorial and commercial work.

Day to Night™, Wilkes’ most defining project, began in 2009. These epic cityscapes and landscapes, portrayed from a fixed camera angle for up to 36 hours, capture fleeting moments of humanity as light passes in front of his lens over the course of a full day. Blending these images into a single photograph takes months to complete.

Wilkes writes in his artist statement:

Day to Night is a personal journey to capture fundamental elements of our world, through the hourglass of a single day. It’s a synthesis of art & science, exploring time, memory & history through the internal & external circadian rhythms of our daily lives.

I photograph from locations and views that are part of our collective memory. Working from a fixed camera angle, I capture what I see, the fleeting moments of humanity and light as time passes. After photographing as many as 1500 single images, I select the best moments of the day and night.Using time as my guide, all of these moments are then seamlessly blended into a single photograph, visualizing our conscious journey with time.

In a world where humanity has become obsessively connected to personal devices, the ability to look is becoming an endangered human experience. Photographing a single place for up to 36 hours becomes a meditation, it has informed me in a unique way, inspiring deep insights into the narrative story of life, and the fragile interaction of humanity within our natural world.

Gaining permission to create the Day to Night™ photograph of the Vatican at Easter Mass was particularly challenging. Wilkes tried for over 2 years without success. Fortunately, one of the priests at the Vatican contacted Wilkes and ultimately connected him with the Instituto Maria S.S. Bambina whose terrace overlooks St. Peter’s Square and Basilica. The location was perfect. Wilkes photographed a total of 1575 individual images and then edited to approx. 50 photographs for the final photograph. Pope Francis appears several times within the photograph.

Commenting on the installation, Professor of Art History and Visual Culture and Special Assistant to the President for Arts and Culture Philip I. Eliasoph, PhD, explains, “Arcing across the magnificently syncopated forms and movements of St. Peter’s space, we are pulled into myriad details peeking into the embracing ‘braccia’ [arms] of the Vatican’s mission ‘urbi et orbi’— to the city and the world. And in the same spirit of Gianlorenzo Bernini’s desire to ‘embrace the pilgrim’ attending ‘Easter Mass’ at San Pietro’s basilica, Wilkes elevates our optical experience with an inspirational revelation. We are delighted that the Fairfield University Art Museum can exhibit this significant artwork in our Barone Campus Center so that students and the entire community will appreciate and enjoy its presence here on campus.”

Day to Night™ has been featured on CBS Sunday Morning as well as dozens of other prominent media outlets and, with a grant from the National Geographic Society, was extended to include America’s National Parks in celebration of their centennial anniversary and Bird Migration for the 2018 Year of the Bird. Most recently a new grant was extended for Canadian Iconic Species and Habitats at Risk in collaboration with The Royal Canadian Geographic Society. Day to Night : In the Field with Stephen Wilkes, a solo exhibitionwas exhibited at The National Geographic Museum in 2018 and in May of 2023 a solo exhibition Day to Night: Photographs by Stephen Wilkes was exhibited at the Fenimore Art Museum in May, 2023. Day to Night™ is published by TASCHEN as a monograph in 2019 and 2023.

Easter tells us to embrace the fullness of our humanity

Rev. Paul K. Rourke, S.J.

Vice President for Mission and Ministry

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so;

For those whom thou think’st thou dost overthrow

Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me…

One short sleep past, we wake eternally

And death shall be no more; Death, thou shalt die.

-John Donne

I find comfort in these defiantly hopeful words from one of Donne’s “Holy Sonnets,” which I first read as a high school freshman. Since last Easter, death has been a persistent and menacing addition to my year. Unexpectedly, I lost my brother, John, last June. Over the last few months, I have lost a friend to a violent carjacking and two Jesuit brothers dear to me and the whole Fairfield University and Prep community: Frs. Charlie Allen, S.J., and Jim Bowler, S.J. I loved and looked up to all these men, and miss them terribly. Death has robbed and humbled me, but I no longer feel in the mood to be deferential. With Donne I feel defiant, and following his example, I say, “Death, I’ve had enough of you!” Surely, Easter is a time for all of us to join in defying death. For our Jewish brothers and sisters, too, the Passover commemorates the Lord’s deliverance of his people from death. The Angel of Death did not claim the first-born of the Chosen People or defeat the Lord’s covenant, but freed the People of Israel from bondage.

The Paschal Mystery the Church celebrates in the Easter Triduum defies death in a singular way: instead of sanitizing or ignoring it, death is confronted head-on and elevated just as it is consigned to oblivion: gory, ignominious death becomes forever the sacrament of our salvation, a reality utterly transformed and transforming. The Risen Jesus is a Wounded Jesus, but his wounds no longer define his destiny: they led to his death, but the Son of God has given them their ultimate meaning: marks of death’s ultimate powerlessness and proof that he will never abandon his humanity.

Whether or not we have tasted much death in our lives, we, too, are wounded in a world simultaneously infatuated with, and in denial of, death. If the news out of Ukraine or Israel and Gaza have not wounded us with grief, then death has wounded us even more grievously: with stony hearts. However we are wounded, Easter tells us to embrace the fullness of our humanity as Jesus did (his own and ours). The voice of Death tells us to fear our weakness and hide our wounds in shame, but Jesus reminds us that God wants to raise, transform, and glorify every part of us, not just the parts we are proud of. He wants to do the same for all of us, and we are commanded to embrace the wounded brothers and sisters all around us with sacrificial love. When we hide from their pain, or ignore their dignity, we keep our tomb closed with the stone of indifference.

When we defy death and embrace the fullness of life God offers (in ourselves and each other), Easter becomes more than another day on the calendar: it becomes the center and meaning of every day. When that happens, we can say in the same joyful confidence of Donne’s poem, “Death, thou shalt die.”

Image by Freepik

An Arts & Minds Podcast with Lori Jones and Carey Mack Weber

Join the Fairfield University arts conversation with Director of Programming and Operations at the Quick Center for the Arts Lori Jones, and the Frank and Clara Meditz Executive Director of the Fairfield University Art Museum Carey Mack Weber.

An Arts & Minds Podcast with Katherine Schwab, PhD, and Philip Eliasoph, PhD

Listen to an Arts & Minds conversation about the future of arts programming at Fairfield University with founding Director of the Arts Institute and Professor of Art History and Visual Culture Katherine Schwab, PhD, and Special Assistant to the President for Arts and Culture, and Professor of Art History and Visual Culture Philip Eliasoph, PhD.

Ash Wednesday + The Perfect Valentine

Rev. Paul K. Rourke, S.J., Vice President for Mission and Ministry

A couple of weeks ago, while waiting to pick up his wife from work, a friend of mine, someone I’d known since high school, was killed in a carjacking. He was a beloved husband and the father of three. We will bury him this Friday.

I share this with you not for shock value or to elicit sympathy, but to share some of what Mike’s tragic death has taught me. I hope it can speak to all of us this Ash Wednesday, because we all live in a world of violence, where the unthinkable can burst into our lives with shocking ferocity. His sudden death has reminded me of the urgency of living life to the fullest, not some time in the future when I get my act together, but right here, right now in all of the uncertainty and flux of life. I have to get my act together now, or at least make some progress toward that end, or, as St. Ignatius of Loyola might advise: at least I need to desire to do so, or desire to desire to do so. Urgency is essential. (That lesson is hard enough when you get to be my age. I understand how much harder it can seem when you’re in college. Nonetheless, Lent reminds all of us that urgency is the hallmark of true discipleship and a meaningful life.)

“Getting my act together” is not about perfection or at heart, a self-improvement project. It’s about living the gospel fully. What does that mean? That I remember how much God loves me and live my whole life from that love—not to win that love, but to live out of it. Some have commented on how ironic it is to have Ash Wednesday fall on Valentine’s Day this year. I think the coincidence is wonderfully appropriate. Our Lenten journey is fundamentally meant to deepen our love affair with God, which can only happen when we realize more fully how madly and deeply our God is in love with us. His love is our Alpha and Omega, the only perfect Valentine we will ever receive.

The Climate Crisis

By Richard E. Hyman

Distinguished Visiting Professional and Adjunct Professor, Waide Center for Applied Ethics, Fairfield University

“The biggest threat to our future is thinking that someone else will lead, that someone else will solve the climate crisis.”

Last year, Fairfield University’s Waide Center for Applied Ethics sponsored a multidisciplinary faculty panel for a university-wide and community discussion about how their respective areas of study addresses issues of climate change and justice.

This event was part of the Worldwide Climate and Justice Education Week, a global initiative led by Bard College, promoting dialogue on climate and justice on campuses and in communities around the world.

Too often climate conversations are restricted to sustainability and climate science programs. To truly solve the climate crisis, we need everyone who is concerned about climate change and our future to talk about climate, and to act: academics, activists, artists, businesses, community members, faith leaders, governments, innovators, nonprofits, students, writers and more.

In 2023, 58,000 people in 61 countries participated in 285 events. Fairfield University was one of them, focused on the critical work ahead, and our shared resilient future. The thinking is that although we cannot stop today’s climate change, if we talk about it and take action, we can better deal with it, mitigate the impact, and importantly take measures to prevent it in the future.

Making climate an event helps students understand that they can make a positive difference with their life’s work. By engaging students in creative, interdisciplinary ways, we can help them explore how climate applies to their respective areas of study and personal interests, so they can learn how to favorably impact climate solutions, both as students and in their careers or avocations.

The following is a selection from each professor’s comments, in the order in which they were presented. Science, business, mental health and ethics will be followed by my concluding remarks.

Calculating Christmas: Hippolytus and December 25th

T.C. Schmidt, PhD

Assistant Professor of New Testament and Early Christianity

Thomas Schmidt’s article “Calculating Christmas: Hippolytus and December 25th" originally published in the Winter 2022 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review and is republished here with permission from the Biblical Archaeology Society.

Many readers will be familiar with the common refrain that December 25, Christmas, was originally a pagan holiday, perhaps corresponding to the Roman festival of Saturnalia or the feast of the sun god Sol. As the chorus goes, the date was chosen for the birth of Jesus to make Christianity chime with a polytheistic society already attuned to December 25 revelry. But is the old song true?

I myself used to sing this kind of anti-carol, but then, while translating a treatise of Hippolytus of Rome, I came across a passage stating that Jesus was born on December 25.1 Now, Hippolytus was a Christian author who wrote in the early third century A.D., and Saturnalia and the feast of Sol were not celebrated on December 25 that early in Roman history; Saturnalia never was, and the feast of Sol only came to be later. So Hippolytus clearly could not have chosen the date to please pagan sentiments.

This discovery was exciting, yet as scholars have long known, the manuscripts of Hippolytus’s treatise are divergent, with some claiming Jesus was born on December 25, but others giving one or two alternative dates. Because later Christians marked the birth of Jesus on different days in December and January, many have concluded that subsequent scribes must have changed Hippolytus’s original dating. These changes then ultimately contaminated the manuscript tradition, leaving us to sort out the mess. In all likelihood, though, Hippolytus did have in mind an exact date for Jesus’s birth—but was it December 25?

Image Credit: Statue of Hippolytus Everett Ferguson Collection | Licensed under Creative Commons 4.0.

Fortunately, an early Christian artifact shines light on this question. I speak of the famous Statue of Hippolytus, perhaps the oldest extant piece of Christan art that can be precisely dated. This statue is now in the Vatican Library and depicts a figure seated on a chair. On the sides of the chair are extensive inscriptions extracted from the works of Hippolytus and dating to 222 A.D. Intriguingly, in one of the inscriptions Hippolytus states that the “Genesis of Christ” occurred on the Passover of April 2, 2 B.C.

Scholars have typically interpreted the Greek term genesis as referring to the “birth” of Jesus, but in an extensive study I have shown that the word most likely refers to the “conception” of Jesus. This is why the Gospel of Matthew says, “The genesis of Jesus Christ happened in this way: After his mother Mary was betrothed to Joseph, before they came together, she was found with child by the Holy Spirit” (Matthew 1:18, author’s translation).

And this is where we must do a little math. A typical gestational period is, of course, around nine months (a fact recognized already in antiquity), and nine months from April 2 is pretty near to December 25. So Hippolytus could have believed Jesus was born on December 25, but did he actually?

What we need is another good clue. Happily, this can be found in a different work of Hippolytus, one called the Chronicon. In this, Hippolytus makes all sorts of chronological calculations involving the dates of biblical events and personages. Careful examination of these calculations makes clear that Hippolytus believed Jesus was born precisely nine months after March 25, the vernal equinox of the Roman calendar. And naturally, nine months from March 25 is exactly December 25, the Roman winter solstice.2

Though it is not certain that Hippolytus believed that Jesus was born on December 25, it does seem to be the likeliest interpretation of the evidence as a whole. What is more, once we see Hippolytus’s computational thoughts for what they are, we can see other ancient Christians making similar calculations, beginning with Clement of Alexandria (195 A.D.) and continuing on with many other later writers. For they too believed that Jesus was conceived on Passover and was, therefore, born approximately nine months later—albeit with some selecting slightly different dates for his birth.

Was Jesus really born on December 25? The current evidence suggests that Hippolytus did not derive the date of December 25 from pagan celebrations, but that he also does not seem to have drawn on any ancient tradition for the actual birthday of Jesus either. Otherwise, why would he and his fellow early Christians give slightly different dates for Jesus’s birth? As I said, some, like Hippolytus, do give December 25, but others place the date a bit earlier or later in December or January.

It seems then that these various dates for Jesus’s birth were chosen because Hippolytus and others thought that God organized and balanced the cosmos so as to ensure that profound spiritual moments would coincide with important points in the solar and lunar year. In this way, such sacred happenings would be literally spotlighted by the various cycles of the sun and the moon. Hence, Hippolytus and most of his fellow Christian writers believed that the date of creation, the conception of Jesus, and the crucifixion of Jesus (or, in some cases, his resurrection) all occurred on the solar vernal equinox, or the lunar Passover, or both.

The oldest and strongest tradition, however, concerns the date of Jesus’s conception, which all the earliest sources agree occurred on Passover. And this very consistency explains the diversity of calendrical dates for Jesus’s birth. This is because the lunar Passover drifts back and forth between late March and mid-April. Given this, the dates for Jesus’s conception (and his birth nine months later) would differ in proportion to the date which an ancient Christian chose for the Passover of Jesus’s conception—for the ancients had much trouble calculating lunar phases far into the past or future and consequently often arrived at slightly different dates. This is why some ancient Christians give the date for Jesus’s birth in mid-December, others December 25, and still others early January, since all those dates are about nine gestational months removed from when they each thought the Passover of Jesus’s conception happened to occur.

So, if this is how Hippolytus and others settled on the day of Jesus’s birth, where did they get the idea that Jesus was conceived on Passover?

This remains a mystery. They may have derived it from even more ancient traditions or from theological beliefs about how God organized the world. What is clear, however, is that Hippolytus’s choice of December 25 for the birth of Jesus won out. His choice must have been helped by the fact that only in Hippolytus’s theory would Jesus, the light of the world, begin to shine on the winter solstice, the darkest day of the year; and only on this day could the carol truly be sung:

O come, thou Day-Spring come and cheer

Our spirits by thine advent here

Disperse the gloomy clouds of night

And death’s dark shadows put to flight.

- Page 1 of 28

- Next »