How a ‘love affair with Black literature’ kept Lansdale’s Black Reserve Bookstore alive

A rise in pandemic reading and demand for works written from the Black perspective or about social justice made a unique moment in time, the owner says.

Listen 1:39

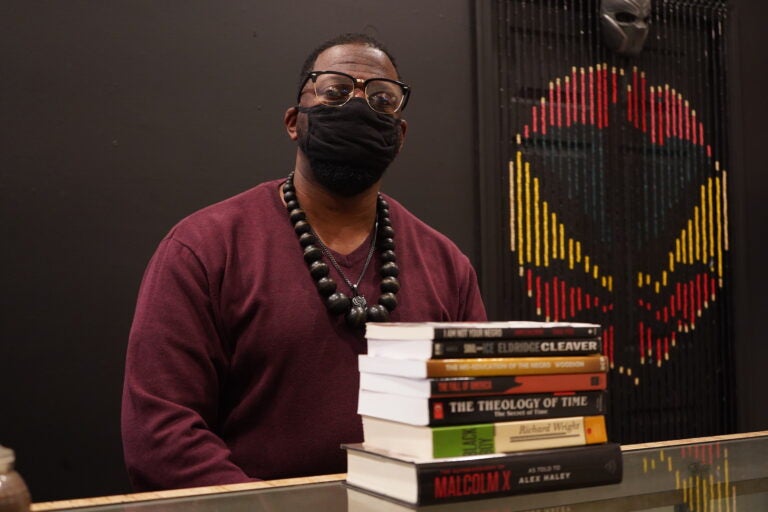

Shaykh Anwar Muhammad, proprietor of Lansdale's Black Reserve Bookstore, recommends anything written by James Baldwin if you are looking to understand America at this moment. (Kenny Cooper/WHYY)

As many small businesses buckle under the weight of the global pandemic and the ensuing economic chaos, one bookstore more than 30 miles away from the hustle and bustle of Center City has found a way.

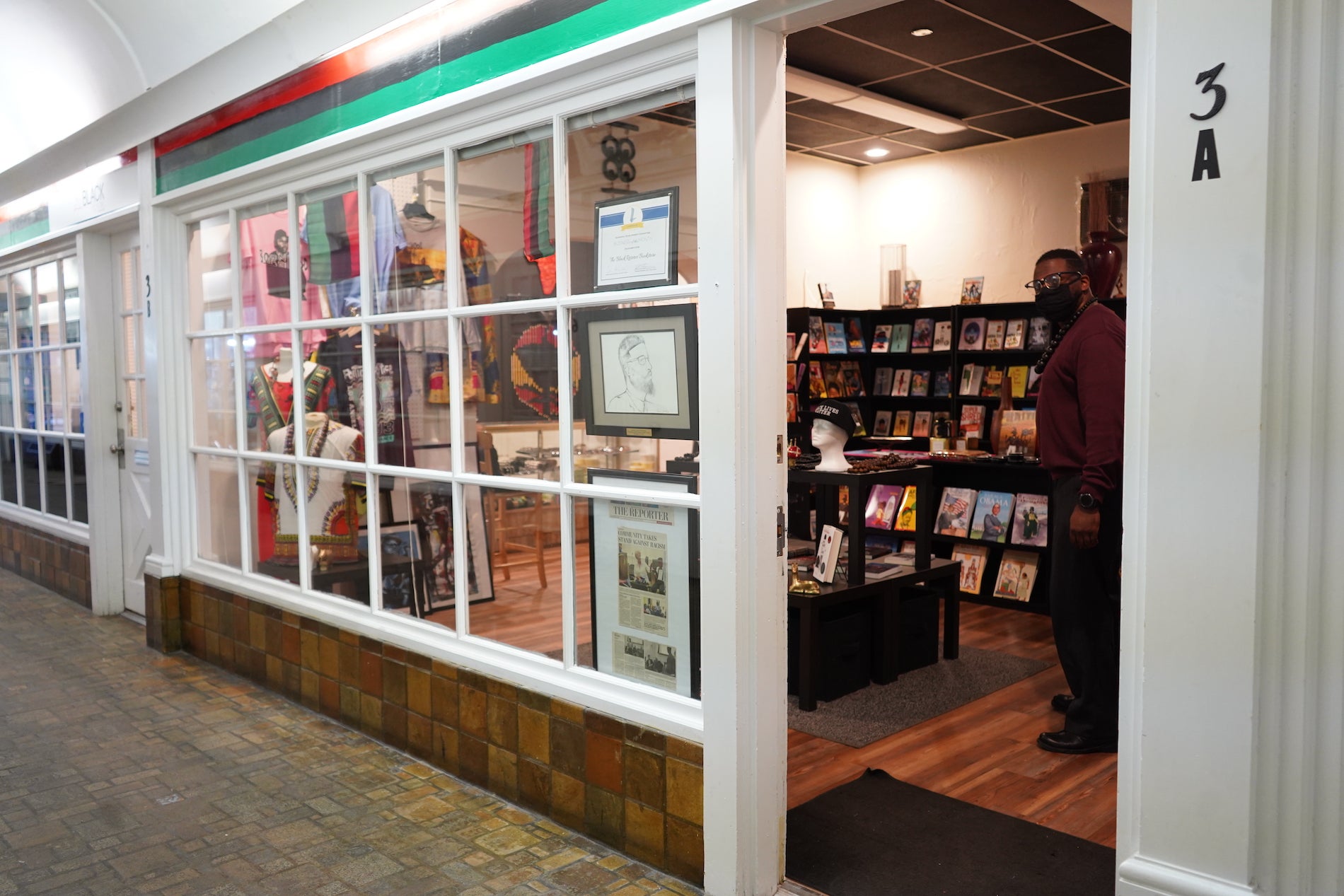

Shaykh Anwar Muhammad, 41, is the proprietor of the Black Reserve Bookstore, specializing in Black literature. The thing that stands out about his brick-and-mortar literary haven is its unlikely location: Lansdale, a Montgomery County town where more than 75% of the residents are white. When the coronavirus sent many businesses packing, people from near and far helped keep the lights on here.

“I do believe that people’s love affair with Black literature aided me in still being open in this time period,” Muhammad said.

Muhammad grew up with a big family in Steelton, outside Harrisburg. His introduction to reading stemmed from economic hardship, he said.

“That was my way of traveling. That was my way of seeing and being exposed to a lot of things, and especially being introduced to concepts and things from a Black perspective that I didn’t even know existed, and it completely opens your mind and makes you think that anything is possible when you start reading these stories,” he said.

After high school, he attended Millersville University, where he studied communications. Although he left for an office job, Muhammad soon found a calling.

“I got involved in working with children. I worked with adjudicated youth for 15 years. I coached high school football. I coached Little League Baseball. I literally did everything that you can do active with children and try to improve children’s lives, especially inner-city youth,” Muhammad said.

He made his return to literature while writing a book of his own. On moving to the area, he noticed a void, so he planned on starting an online bookstore.

“And then I thought about because of the lack of … Black culture in this area, [I] actually thought about doing an actual brick and mortar,” Muhammad said. To obtain Black literature, apparel, soaps, and things of that nature, he was told that he needed to take a 30-minute drive to Philadelphia, something he characterized as insane.

Though his store began, in part, as a half-hour shortcut, the catalyst for opening was representation.

“I’m a firm believer that you can’t be what you don’t see,” Muhammad said.

He wants to be a role model to all kids, and along with representation comes a sense of belonging, he said.

“In this area, I didn’t feel that there was a place where Black people could just go to be Black, and just be themselves — and I know we need those spaces,” Muhammad said.

Since opening in 2017, the Black Reserve has outgrown several of its workspaces on West Main Street. Satisfied customers give it five-star reviews online.

“Owner is building a community. Passionate, kind, knowledgeable. A unique experience full of good books and conversation. You won’t be sorry you went,” one wrote.

“His enthusiasm for the books was refreshing and contagious,” another said.

“I will definitely be back for more conversation with Mr Muhammad … and, of course, more books,” another wrote.

Though the reception from the Lansdale community has generally been warm, including a local business award, reaction to the store has gone both ways.

“I was getting mixed reviews, as far as some people were saying how it was racist that they have a Black bookstore, because there are no white bookstores,” Muhammad said.

He wants to make one thing clear: The Black Reserve is not a Black bookstore. The store just happens to specialize in Black literature.

“When I go to bookstores … and say, ‘Where is your Black section or your African American section?’ they would direct me to where the books were on the shelves, usually a very small section, right? One or two shelves,” Muhammad said. “So you’re telling me that everything that Black people wrote in the history of literature can fit on two shelves, right? So that bookstore is 99.8% white. So what do they call that bookstore? They don’t call it ‘the white bookstore.’ They call it Borders and Barnes & Noble.”

Reaching beyond Lansdale, too

Although the Black Reserve does not have the resources of a large operation like Barnes & Noble, that hasn’t stopped Muhammad from reaching bookworms.

“I have shipped books everywhere — California, Colorado, Texas, Florida. Like literally everywhere. It’s been amazing,” Muhammad said.

At the start of the pandemic, he was forced to close his doors and shift completely online. And while many businesses struggled, the bookstore found a niche as people began to gravitate to reading.

“When the pandemic first hit us, in our infinite wisdom, a lot of people felt that they would just go home, they would lock themselves in their homes, and they would just watch Netflix the entire pandemic, or they would watch cable,” Muhammad said. “But an amazing thing happened: A lot of people started contacting me for books and literature, because I know they were getting tired of just sitting around watching movies and watching TV all day.”

Around the time the store was set to open again, anti-racism protests were happening nationwide. And with those protests came a particular interest in Black books.

“So a lot of people were, I would say, trying to improve themselves, or improve their understanding of what was going on. And what better place to improve your understanding of what’s going on, especially from a Black perspective or with social justice issues, than a bookstore that specializes in Black literature,” Muhammad said.

Soon, he began selling out of books, including some that were out of stock at the larger bookstores.

With anti-racism book clubs all the rage, newer white customers even came to the store with lists, trying to find books like “How to Be an Antiracist,” “White Fragility” and “The New Jim Crow.”

“So when these books came out, they only came up with a certain number of them because … they weren’t that popular, right? I mean, some people got them,” Muhammad said. “Everybody wanted them. You couldn’t get them on Amazon.”

When customers found out those books were not available, he began to recommend that they read the classics. From James Baldwin and Richard Wright to Malcolm X and Assata Shakur, there’s a list of Black writers whose catalogue is perfect for the moment we are living in, Muhammad said.

He believes there was an inevitability to the events that transpired last summer.

“That’s one of the biggest problems with race relations. In any relationship, for a relationship to bloom and blossom and to be amazing, it takes a mutual exchange of information. It can’t be a one-sided story,” Muhammad said.

And a one-sided story is written all over Lansdale, a place where Confederate flags are not hard to miss, he said.

“The first step to recovery is that you first have to admit that you have a problem. I think for the longest time in this area, they believed there wasn’t a problem. But you only believe there wasn’t a problem because everybody looked like you,” Muhammad said.

In a pandemic-less world, Muhammad holds community outreach events at which he talks to youth in the area. Through those conversations, he said, he has learned of implicit biases negatively affecting Black students around the neighborhood.

“It’s hard to hear a young person, a child … feel so defeated due to their experience inside the schools … And one of the biggest misconceptions is that Black children that live in the Greater Philadelphia area have it all together, and our parents have it all together,” Muhammad said.

The plight facing Black students in the schools is making them want to leave the community after graduating, according to Muhammad.

“Things are not fine,” he said.

However, he was genuinely surprised to see protests around the neighborhood. “That’s fantastic, because that tells me that something happened to a Black person and white people finally said, ‘Hey, that’s messed up.’”

As a resident of nearby Hatfield, Muhammad said that his criticisms of the community come from the heart.

“I think people glaze over this fact about me and this area. I’m fully locked in here. My business is here. My family is here. My house is here … I am dug in. I’m fully vested. I’m not speaking about Lansdale from an ivory tower. I am Lansdale. I am this area.”

He wants protests and conversations to be more than a fad. He wants them to have a long-lasting impact on the broader community and his family, including his 8-year old son.

“In 15 years, if he’s standing on Main Street talking about his life matters, then we’ll have all failed him.”

Show your support for local public media

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.