This article was shared by our partners from Pinkbike.

Innovation is a tricky business. Many of the technologies that have made mountain biking as good as it is today (suspension, dropper posts, disc brakes…) were once considered unnecessary and over-complicated by some. But on the other hand, if you look back at a magazine from a few years ago you’ll see no shortage of “game-changing” innovations that never amounted to much.

Neither Kazimer nor I were impressed with the $1,975 Trust Shout.

A tube in a tube in a tube in a tube, what could possibly go wrong?

To name a few, how about linkage forks, one-piece wheels, pull shocks, multiple shocks, or the Specialized’s WU dropper posts that adjusted the saddle tilt as it dropped… Some of these were good ideas in many ways, but the fact they failed to take off suggests they weren’t as much of a game-changer as their inventors hoped, or perhaps were too complicated to be worth the effort.

Looking back in time, it seems easy to sort the revolutionary innovations from the duds. But hindsight is 20/20. Spotting what’s going to move the sport along in future (and what’s not) is much trickier.

So which of the current crop of tech trends are worth having? I’m going to play the role of the bad guy in Gladiator and sort those that deserve to live from those we could probably live without.

Bear in mind, this is just my current opinion and I’m both willing and likely to change my mind about some of these ideas. It isn’t meant to rain on anyone’s parade and I certainly don’t want to discourage innovation; it’s just a finger-in-the-wind take on which ideas I think we’re likely to see more of in future. Who knows? Looking back on this list in ten years’ time I might have got it all wrong.

Six-bar suspension

To recap, a four-bar linkage is one where the rear axle is mounted on a frame member which is not directly connected to the mainframe, but moves on two other links – these could be a pair of short links (like VPP) or a rocker link and a chainstay (Horst-link). That makes four frame members: the mainframe, lower link/chainstay, rear triangle/seatstay, and upper link.

A six-bar linkage adds two more frame members and three or four more pivot points. This adds weight and cost, along with more parts to service. I haven’t seen a satisfyingly specific justification from any six-bar proponents, but the claimed advantage usually has to do with fine-tuning the axle path and therefore the anti-squat curve in a way that isn’t possible with a four-bar design. But whether that makes the bike ride appreciably better is highly questionable. After all, there’s little agreement on what any of these curves should ideally look like anyway.

What’s more, according to Pinkbike’s kinematics expert, Dan Roberts, some of these designs are extremely sensitive to pivot placement, to the point where manufacturing tolerances could (potentially) create a meaningful change in those highly-refined kinematics.

Verdict: Unnecessary complication

Long-travel droppers

Like many people, there was a time when I had just about convinced myself a 125mm dropper was all you needed. Sure, the saddle got in the way sometimes (actually quite often) but that probably just meant I wasn’t hanging far enough off the back of the bike, right? Then every time I tried a longer post – first 150mm, then 175mm, then 200mm and more – it felt great to have a bit more room to move around and allow the bike to come towards me when pumping. When I returned to a shorter seatpost, the saddle always seemed to be in the way more often than I noticed before.

Some people blame steep seat tubes for the need for more drop, but I think the move to longer front-centre lengths is a better explanation because you can’t hang your weight behind an over-extended saddle if you want the front wheel to grip. Really though, long-travel droppers were always a great idea – judging by the wear marks on the last fixed seatpost I ever owned, I was dropping it by about 200 mm by preference. It just took time to make a reliable dropper that long.

Verdict: Useful innovation

Through-stem cable routing

When it comes to regular internal cable routing, most manufacturers have managed to eliminate the rattle and make it relatively easy to change a cable. But recently Magura launched a concept for a brake with cables running through the handlebar, then Focus launched several new bikes with cables running through the headset, spacers and the stem.

I hardly need to tell you the drawbacks of this. Swapping a cable means taking the stem apart and changing stem length involves taking the brake apart and re-bleeding it. Even dropping the bar height requires a different (round) spacer above the stem, which means different parts and a less-than-clean look, which sort of destroys the point. Having a few cables crossing in front of the frame is fine.

Verdict: Unnecessary complication

Tire inserts

Inserts aren’t for everyone. Regular tires offer enough protection for most people and if you’re worried about pinch punctures or rim damage you could just increase pressures slightly. But if you’re after the best possible grip, they have real benefits. Not only do they add some protection for your tires and rims, allowing lower pressures, they also increase the damping of the tire, making it less bouncy, more stuck to the ground.

You could achieve much of this with a thicker-casing tire, and doing so might have a similar weight penalty to adding an insert. But here’s the thing: thicker tire casings dramatically increase rolling resistance, which has a much bigger effect on rolling or climbing speed than the extra weight does. But with an insert, you can have the protection and damping benefits without the slower rolling speeds.

Verdict: Useful innovation

High pivot trail bikes

I’m sure this will be controversial. I get that high pivot bikes have advantages – they’re better at absorbing large bumps and have better sensitivity while pedalling. If you’re looking to get down a World Cup track as fast as possible, they make a lot of sense. But even then, it’s not as if low-pivot bikes aren’t still winning races and when Neko Mullaly tested comparable high and low-pivot bikes in a really impressive batch of back-to-back testing, there wasn’t much in it. It even sounded like he was leaning towards the low pivot bike.

I’m not saying high pivot bikes aren’t better for descending (for a given amount of travel, I think they are); I just don’t think the benefit is worth it for anything other than a downhill race bike. Manuals and bunnyhops are slightly harder work, the idler adds a measurable amount of drag, it adds weight and complexity, plus you’ll usually need a longer-than-stock chain and a lower roller guide to keep the chain growth in check.

Are these downsides the end of the world? Absolutely not. But the upsides aren’t going to change your life either, so I’m not convinced it’s worth it for a bike you pedal under your own steam. If you’ve already got 200mm+ of suspension travel then fair enough, but otherwise it might be simpler, more efficient and more effective to just increase the travel in order to improve big-hit absorption.

Verdict: Unnecessary complication

High-volume air springs

While coil springs have the same stiffness throughout the travel, traditional air springs are much stiffer at the start of the travel than in the middle, which can make them feel harsh, unpredictable and unstable. But by increasing the volume in the positive and negative air chambers, it’s possible to reduce this mid-travel dip in stiffness, making them perform more like coil springs, with the associated traction and support.

When companies advertise this “coil-like feel”, people often ask “Why not just use coil springs”? Well, they’re heavier, usually aren’t progressive at the end of the travel, and most of all, changing the spring rate is incremental, expensive and time-consuming. And from a brand’s perspective, getting all their customers set up with the right spring rates is a logistical headache. That’s why air will continue to be the default option, especially as air springs continue to improve.

Verdict: Useful innovation

Electronically controlled suspension

Last year saw the release of RockShox Flight Attendant. Though not the first, it’s the latest and greatest automatic suspension mode selector yet. It improved on Fox Live Valve and Lapierre’s ei system by making it wireless, pedal sensitive, and offering an intermediate compression damping mode as well as open and closed.

The idea, of course, is to allow you to have a firm and efficient bike when climbing, a supple bike for descending, and something in-between when you’re pedalling through rough terrain. And according to Kazimer’s review, it basically does what it sets out to do.

But even the original Fox Live Valve worked exactly as intended most of the time. My issue with automatic lockouts in general is that, with modern bikes, having the suspension locked out is only a minor benefit unless you’re out of the saddle sprinting – less than 1% faster according to this test. And for the longer climbs where that kind of percentage could add up to a few seconds, what’s wrong with using the lockout manually?

Don’t get me wrong, the technology is impressive. But given the marginal benefits (especially when compared to a cheap remote lockout), I struggle to see the appeal unless the price, weight and charging requirements come down considerably.

Verdict: Unnecessary complication

Wide range cassettes

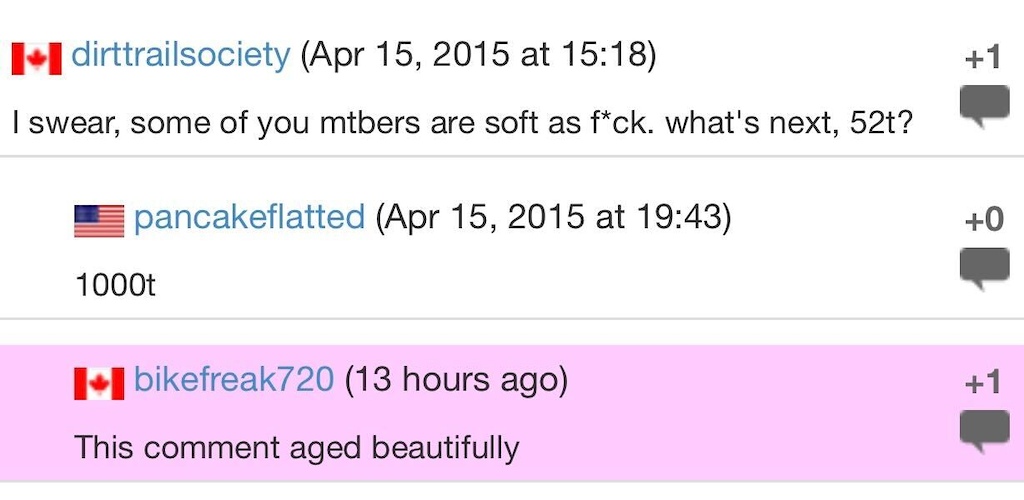

I realize the comments section is full of world-class athletes who can ride a singlespeed all day long up 25% inclines. Many of you might think that a 52-tooth bottom gear is totally unnecessary, but science says otherwise.

Let’s imagine you’re a 70 kg rider with a 15 kg bike and you want to ride up a 20% gradient (which is steep but not unheard of). Let’s say you can sustain 360 W of power, which at that bodyweight is about the level of a male domestic pro cyclist. On a 20% gradient in ideal conditions, you could sustain a pace of 7 kph.

When working hard, most cyclists like to pedal with a cadence of about 90 RPM. With a 32-tooth chainring and a 29″ wheel, you’d need at least a 56-tooth sprocket to achieve that cadence at 7 kph.

The point is, even very fit cyclists can benefit from large sprockets if the gradients are steep. It’s not that riding hills that steep is impossible with a smaller cassette – I used to run an 11-36t cassette and got up (almost) all the same hills I do now – it’s just that you’ll have to use a less efficient cadence which is more tiring and harder on your body. Besides, gears shouldn’t be designed for the fittest riders in optimum conditions, but to accommodate most riders in most conditions. If you think a 52-tooth sprocket is unnecessary, you’re either not riding very steep climbs or you’re putting up with a less-than-ideal cadence.

Verdict: Useful innovation