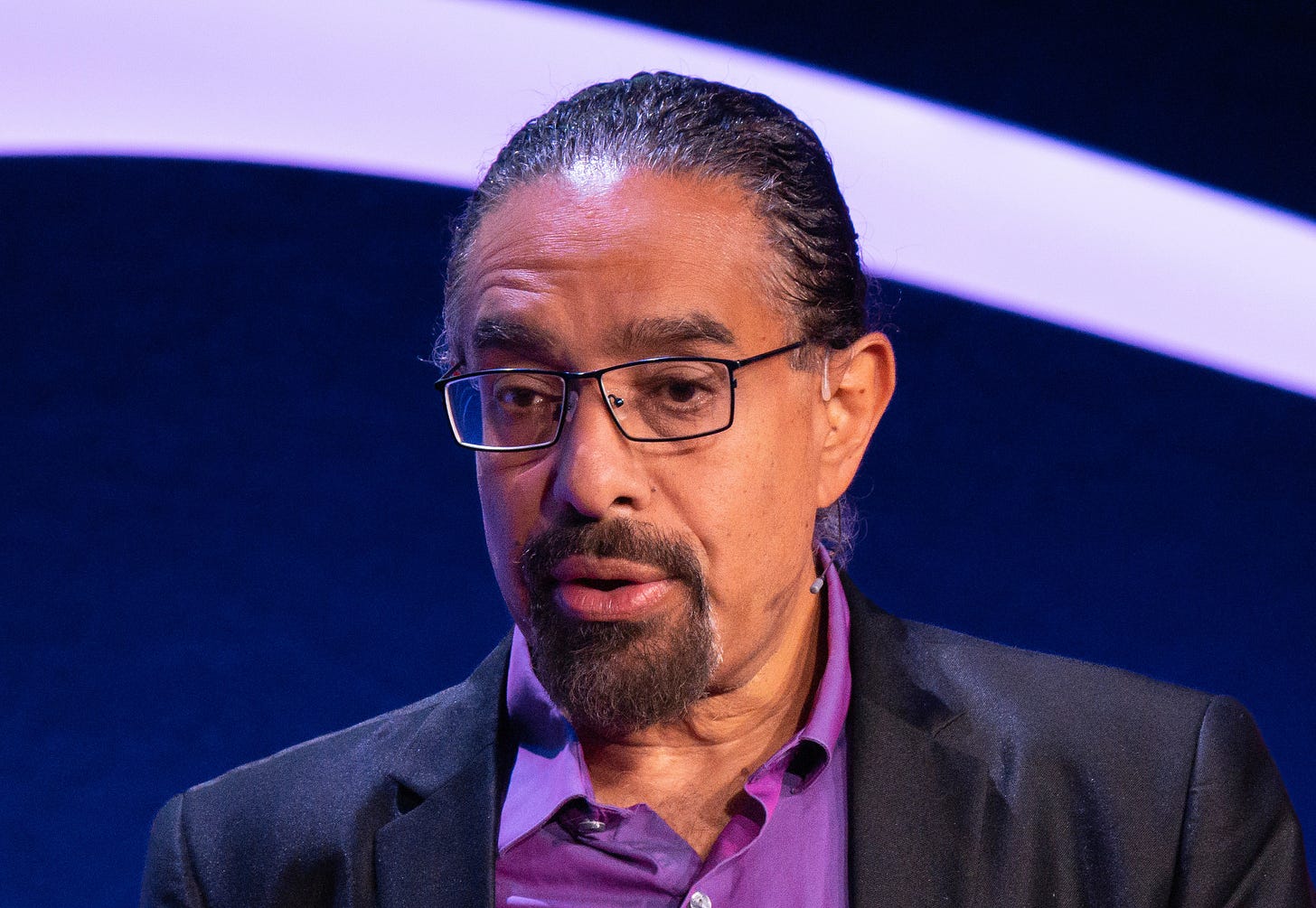

In this episode, I have a conversation (IRL!) with longtime energy analyst Ramez Naam about a wide range of nerdy but fascinating topics.

Text transcript:

David Roberts

As I previewed a few weeks back, on Wednesday, June 28, Canary Media held a live event in the downtown Seattle home space of beloved local independent radio station KEXP. It’s a gorgeous space, with a coffee shop and a small vinyl store, well worth a visit if you make it up this way.

In addition to a lively panel about the IRA and plenty of mixing and mingling with a fascinating, diverse crowd of energy nerds, the event featured a conversation between me and energy analyst/guru Ramez Naam.

We had a wide-ranging discussion covering everything from hydrogen to space-based solar power to geoengineering. Then we opened it up to Q&A and got a bunch of geeky questions about grid-enhancing technologies and performance-based ratemaking. It was so fun!

As promised, it was recorded for all you wonderful Volts subscribers. Enjoy.

David Roberts

I just wanted to say before we started, I should have thought in advance how to say this delicately. A lot of us have been to a lot of energy events, a lot of us old hands, and especially in the early years, we got very accustomed to seeing seas of gray hair at said events. And so it's just such a thrill that things have come as far as they have and this room is full of exciting young people doing cool stuff. Makes me feel old, but it's a small price to pay.

Ramez Naam

Are you saying that we're old now?

David Roberts

Yes, I'm afraid, yeah, if you do the math. Also, this is being recorded for my podcast. This will be an episode of Volts. So maybe everybody in the room say hi to Volts listeners at home. You could have been here, but you were too lazy. I'm joined today by Ramez Naam, who is a longtime energy guru I guess would be the word, forecaster, VC guy, now author of books on climate change and Sci-Fi books and other books, speaker, et cetera, et cetera. Somebody I have been looking to for wisdom since I started this back in the dark ages.

So I'm excited to talk just about sort of where things are now that we've been in this game for 20 years and how things have changed and sort of what's next? So the way Mez came to my attention, and I think a lot of people's attention in this world, was a 2011 blog post in which Mez said, here's the rate at which solar is getting cheaper. I'm going to make the bold prediction that it is going to continue doing that, which you'd think wouldn't be that revolutionary of a thing to do. But anybody who knows energy forecasts knows that as long as there has been solar, there have been people forecasting that it's going to stop getting cheaper, that it's going to level out, it's going to plateau.

If you look at the forecast, it's just plateau, plateau, plateau. And the reality is just down, down. And Mez just said, yeah, it's going to go down. And if you just project ahead on existing learning curves, you get what looked like ludicrously optimistic projections, which you then updated in 2015 and then updated again in 2020, and both times found that despite having been decried for ludicrous optimism, prices had in fact fallen farther than your forecast. And you did a similar post on batteries, more or less, with the same structure. So I guess the way since, I think we agree that solar, wind and batteries are going to be the core of the electrify everything century, I guess my first question is just do you think solar is going to keep doing that?

Ramez Naam

Yeah. Well, so first, David, it's awesome to be here. We've been together for twelve years now and we met basically on Twitter, arguing with this stuff back then. So, yeah, in 2011 I wrote a piece for Scientific American, a blog post, and at the time, the IEA International Energy Agency had a forecast for solar costs, said the cost of solar would drop by about half from 2010 to 2050. And my forecast was very naive. I'm not that smart. I was very lucky. I came from tech, where we have Moore's Law, and so I just applied the very same sort of very dumb learning model to solar.

And because I didn't know enough about energy to know how I was going to be wrong, it worked, more or less. So my forecast was the cost of solar would drop about a factor of ten to 2050, and it actually dropped twice as fast as I thought it would. And again, there were various things wrong in that model and I've updated them since and found where the errors are, I think. Will it keep getting cheap? The future is uncertain, but the odds are yes. So my personal forecast is the cost of solar will drop by another factor of four by the time solar is about a third of all electricity generation on Earth, something like that.

Now, could it be twice as fast? Maybe that's pushing it. Could it be half that rate? Yeah, but it's already the point, so I think it is clean electricity, especially solar, and now batteries have gone through, they're entering their third phase. The first phase was all of history from the 1970s to 2010, 2015, they were in their first phase. That was totally uncompetitive, totally policy dependent. Then with a second phase where new electricity from solar to wind became cheaper in some parts of the world than building new power from gas and coal, at least during the hours of the sun shone, or that the wind did, and that's their second phase cost competitive, and now they're into their third phase.

We've seen this like next era, started saying this in 2018, 2019, they hit this phase where the cost just on a pure kilowatt hour basis of, let's assume new solar, new wind would be cheaper than the operational cost of an already built coal or gas power plant. And that's happening. That happened in Indiana, it happened in Texas. Again, it doesn't deal with intermittency and what you do when the sun goes down and so on. But it's on a bulk electricity basis and there's every reason to believe this will continue. Now, solar is the fastest of these technologies.

Batteries are nearly the same pace. Wind is like half the pace. And wind has various problems, doesn't scale as fast. Hydrogen electrolyzers are going to look like batteries. I think. Batteries and EVs, EVs are still in their first phase. They're still more expensive than gasoline cars, but they are plunging in price and growing in scale at twice the pace of solar. So I do think there's lots of reasons, not in every single clean tech, but in those and the ones we make in factories, mass produce in high volumes, simple single part items, if you can, that those will have a very, very rapid learning rate for decades to come.

David Roberts

Good stuff. So, one of the big questions about the electrify everything model is wind and solar variable. Even with batteries, the batteries we have today, you can get two, four, maybe six, eight hours out of lithium-ion batteries, but you still have variability to deal with. And so, there's this idea that sort of you're going to get to, depending on who you ask, 60, 70, 80, 90%, and you're going to have to fill in the remainder with something else. And it seems to me whether that's 60% or 90% depends a lot on just how cheap solar and wind get.

So, how far do you think electrify everything is going to go? Do you think these learning curves are going to be so far and so fast that we're going to end up needing less of that supplemental stuff than is currently forecast?

Ramez Naam

Yeah, it varies on a variety of things. It varies on geography. So, for instance, Europe is harder to power with renewables than the US. The US has more sunshine and solar gets cheap the fastest. Europe or Japan or Taiwan or South Korea are these places that have winter peaking systems and don't have a lot of sun. So, they're more dependent on wind. It doesn't get cheap as fast. It also matters how big the grid is. Like if we built a Chinese scale grid in the US, you could have solar going from New Mexico to New York. You could have wind from the great plains going out to the coast.

But if we don't get transmission built, and right now we're sucking at building transmission in the US, then powering New York in winter is actually really hard. So, those are like big variables. And in general, I have my opinions on what I think is going to get cheap the fastest. But I'm in general a believer in let's have more tools in the toolkit than we think we need because some of them are not going to pan out in certain areas. So, let's invest in all of it. Let's invest in small modular reactor, nuclear, nuclear fusion, transmission grids, ultra long duration energy storage, power to hydrogen.

Let's do all of it and be in a certain way of more tools than we need rather than fewer.

David Roberts

All right, you're doing all the above cop-outs. I'm going to push you on this. You have solar wind and battery, you have your variable core, and then you have your supplements to even out the power, smooth out the power. Right now, what's going to occupy that role, that supplemental role is up in the air, could be a lot more storage. It could be, as you say, a lot more transmission. It could be some sort of clean, firm power like geothermal or small nukes. It could be small natural gas plants with CCS, which is what you see in the models.

In the big models, they have truckloads of natural gas with CCS all playing the same basic role, which is evening out the variability of renewable energy. So, I want to know, yes, we want to invest in everything. Yes, we want to pursue everything, yes, we want to keep our options open. But in your opinion, what is the mix that's going to play that role?

Ramez Naam

The most underrated of those technologies is ultra long distance, like coast to coast, continent scale transmission. It's probably the one that has the best upside and the most certainty that we can do it. But it's blocked not by economics, not by technology, but by permitting, fundamentally. And we're not doing a lot on there, I think clean firm, whether you call it nuclear vision, SMR vision, fusion, geothermal everywhere, ultra deep geothermal can get power. Any place on the Earth has a big role to play. Ultra long duration storage is a wild card. Like twelve-hour storage, I'm convinced, is like that's going to be solved.

But in Europe or on the US east coast, you need weeks or months of storage. And we don't think there's a few technologies that might do that, but they're wild cards right now. I think offshore wind has a huge role to play. And floating offshore wind is one of the most underrated technologies because in deep water you basically can't do bottom out offshore wind. So around Japan or the US west coast, I think floating offshore wind is probably also a massively underrated technology. And then my very favorite total wild card in these that nobody believes in really, but me, is space-based solar.

David Roberts

I knew it.

Ramez Naam

And that one, my friend Greg Rainey has been talking to me about space-based solar for a decade and I'd be like "No no no, Greg, 20% of the Earth's land area is desert, space launch costs so much why would we ever do this?" But in space, there's no clouds. You can just have it. You can get 24/7 power. You can beam it to Earth as microwaves that penetrate clouds and rain. And some models show it getting in at like two or three cents a kilowatt hour. Based on things like how cheap Starship is going to make launch cost, we think.

Right. And isn't space — it's getting cheaper, right? Getting up to space rapidly getting cheaper?

Space launch is getting cheaper faster than solar. Only two things in history have gotten cheaper faster than solar to date, which are computing and gene sequencing, or gene printing. But right now, we're in a phase where the cost of space launch is actually dropping faster than the cost of solar. And so, that, and then you have this other advantage: if you beam power back to Earth with microwaves — there's a variety of challenges with it, let me tell you. There are a lot of challenges — but if you beam it down to the same intensity as sunlight, rectennas are like three or four times as efficient, so you get four times the power for the same land area, and it works in winter.

So that's my personal wild card. There's like six startups in the whole world doing it.

David Roberts

Has there been solar power transmitted to Earth from space, like, as it actually happens?

Ramez Naam

No. And there's various problems with it. So we've had the first experiments of transmitting — we have lots of solar in space for satellites — and we have the first experiments happening for transmitting solar from one satellite to another. But the big problem so some startups are using lasers. Lasers are BS, because lasers don't penetrate clouds and rain. So why would you do it? Doesn't matter, but one of them just raised a bunch of money. Whatever. The way to actually do it is microwaves. But the problem with microwaves is, if you want to hit a target on Earth, you need these kilometer square arrays in space, and no one's ever built anything of that size in space.

So if you want Sci-Fi that's totally Sci-Fi.

David Roberts

And do you fry the birds? Do you fry the birds?

Ramez Naam

You can transmit it, I mean, you could if you're really good.

David Roberts

If you wanted to.

Ramez Naam

No one can get that good. No one can get that good at beaming microwaves yet, but you could transmit it at like, one sunlight intensity, but get three or four times the energy on the ground in the same area. So getting to where you can fry birds is actually a really really hard problem. It's not the problem that we have right now.

David Roberts

Interesting. And this brings up my lonely wild card. Since you're talking about lonely wild cards, the one that only I seem to care about, which is wireless charging of electrical devices, which I always thought conceptually solves all kinds of problems. I can just imagine power transmitters seeded throughout your city and every electrical device having a receiver able to receive power through the air. I mean, those technologies exist. Like, you can power something at a distance now, even at a reasonably large distance. There are, like, sonar versions, laser versions, there's X-ray, weird X-ray versions. I just thought, like, cut the cord, all these charging difficulties go away.

Basically, everything electrical is charging all the time. When I do my little "the future" meme, the future world we're going to have meme, like, it's all wireless charging. Do you have an eye on that? Is anything happening there? Do you think that's going to go anywhere?

Ramez Naam

I have a little bit of an eye on that, but it still doesn't solve all the problems because it's really hard to do super long distance again unless you build these — if you want to penetrate clouds anyway — unless you build these kilometer square transmitters. So I think for a short range, like within our room, there are potential or maybe for, like, mountaintop to mountaintop. But getting it across a continent without bouncing it in space is really hard, I think.

David Roberts

And you are in tech, really, and not really in politics. But I'm curious what your take is. I wouldn't say that IRA has taken care of the funding problem. I mean, I think we still need a lot more funding for everything, all the time, everywhere. But there's a huge accelerant now, at least in terms of money. So what do you see then, when you think about the US decarbonizing? What are the big remaining barriers that worry you?

Ramez Naam

It's a really good question. I'd say, like, the IRA is just part of the puzzle. It's interesting. The IRA is understated. It's not $450,000,000,000 of federal spending a year. It's like trillions. Because the IRA is not a pool of money, it's a per unit subsidy. And forecasters always do what on unit forecast. They always underestimate it.

Audience Member

Right.

Ramez Naam

So the actual size of the IRA is actually much larger.

David Roberts

I think Goldman Sachs said 1.3 trillion, I think was its number, as opposed to the official number, which was 3.9 billion or 300 and something billion, but a lot more than the official forecast.

Ramez Naam

Yeah. And I think the IRA also we talk about the US, but let's think about this globally, like, three big things happening in global climate policy over the last few years. China has further put its foot on the accelerator. India has done some I won't even count that. Vladimir Putin invading Ukraine. Putin is, like, now a climate hero. He's an asshole, but he's done all this work because we thought natural gas was going to be the last fossil fuel we got off of. And Putin thought the natural gas exports to Europe, he had Europe over a barrel. But instead he's accelerated the pace, which Europe is getting off of gas, deploying more renewables, ultra long duration storage, hydrogen funding, fusion, all this stuff.

So those are equally big. And the IRA is really big. What does the IRA and by the way, in the US. We talk about the IRA. We don't talk enough about state level policies. 29 states in the US have a binding RPS or CES. Right. And that started before the IRA, and it's actually potentially even more impactful. What does the IRA not solve? It doesn't solve permitting. And that's actually like the Achilles heel that we have. And we talk about permitting. There's a strain of environmentalism that is like "don't build it environmentalism", and that's going to kill us.

That's the biggest political barrier we have in the US. Is that it's so dang hard to build things. And people talk about NEPA reform, whatever. NEPA is just the feds. Like, if you want to build something, it's this internested issue of multiple federal agencies and then multiple states and then county level and city level and every property owner. We just had the first interstate transmission line in the US. The biggest one, approved, like, two months ago, I think Arizona to California. I think it's an $8 billion project. Okay, we spent trillions, right? That $8 billion project took 18 years to get approval from multiple states, multiple counties, landowners, and so on.

If that's the pace, we're just in a world of hurt. So what do I think the most important thing we can do in policy in the US is get out of the way and allow stuff to be built. NIMBY is like the death of the world if we don't stop it.

David Roberts

Yeah. This is going to be an interesting tension. I think there was a great article in Heatmap about it just this week. Everybody should be reading Heatmap.

Ramez Naam

Eric has an opinion on that.

David Roberts

After you're done with Canary. You should read Heatmap. And I not just toot my own horn, but I wrote about this back in 2012 or whatever, but this distinction between climate hawks and environmentalists is, how I put it, people who are primarily focused on decarbonization, people who are primarily coming out of the environmental movement with all its sort of associated commitments and whatnot. And I think this is going to be a huge tension, but it's also — do you worry at all, maybe you don't worry, I worry about a lot of the people who are yelling about permitting, want to cut down environmental review because they don't care about the environment and want more oil and gas and don't this is all bad faith from one large portion of this debate.

Do you worry about being on the same side with a bunch of bad faith jerk offs?

Ramez Naam

I think the bad faith the bad faith actors, the actors that want, like, permanent reforms they can build more fossil fuels are on the losing side of history. They're betting on a technology that fundamentally is going to lose on cost. So I say let it come, like, in an open playing field. If it's easier to build pipelines and transmission lines. Clean electricity is going to win. So I'm totally happy taking that deal. Bernie Sanders disagrees. Right? Like he voted against the Schumer-Manchin permitting reform bill that you had one Republican vote for because he's so obsessed, obsessed with don't build fossil fuels.

Well, guess what? Building more renewables is actually more important than not building fossil fuel. On a competitive basis, at least my bet, the clean energy just wins on cost. So like open the floodgates, let it in and clean energy is going to win is my personal viewpoint on that.

David Roberts

What do you make of this? Just came out another version of information that's come out over and over again over the years, which just shows that fossil fuels are not declining globally. They're not declining. We are adding on to the total energy load of the world that's what renewables are doing is increasing the total. But the actual amount of fossil fuels is not declining, which leads a lot of people to say building new renewables is not enough. We have to cut off supply at some point. What do you make of that argument?

Ramez Naam

So, I think you have to look at leading indicators and trailing indicators, and the leading indicator is cost. What's going to win economically? The next derivative is like the pace of deployment increase, and then actual deployment and actual deployed stocks is a super trailing indicator. So, you look at this and ask, are we growing renewables fast enough now? Are they undoing fossil fuels? Well, actually, we might have passed peak fossil fuels in the power sector in 2022. All the growth we have not yet shrunk the internal combustion engine car fleet. But what was the — anybody want to guess? — like, what's the year in which sales of gasoline-powered cars peaks? Can we have a guess. 2017, 2018. It happened already. Now we want it to go down faster. We want retirements of ICE cars to be faster than deployments. But all the growth in vehicles and passenger vehicles is electric. So, have we peaked yet? No. And I think we'll have peak total fossil fuels and peak emissions sometime later in this decade towards 2030. It's not fast enough but the writing is on the wall. Like fossil fuels are primarily dead men walking. It's just a matter of how fast can we pull it off.

David Roberts

So, let's talk —

Ramez Naam

I'm very opinionated here, but that's just what the math says.

David Roberts

So, let's talk then about the hard to abate sectors then because they're the ones I wouldn't say we have electricity in hand, but we have a sightline to where we're going on electricity. We have a sightline where we're going on transportation. We have a sightline in buildings, although this crowd is full of people who will tell us all about the many complications of doing what we know how to do in buildings, but we know how to do what we need to do in buildings. But there are these legendary, difficult to decarbonize sectors. So, two questions.

One is, do you think they still warrant that term? Do you think they're still difficult to decarbonize? And which of those worry you?

Ramez Naam

Yeah, they are. And so I should say that what I've been saying is mostly related to power and ground transport. That's where we have really, really fast linear rates. But if you add up ground transport and power, you've got maybe 45% of global carbon emissions. Right. The really big ones are industrial emissions. Rahul talked about cement, my math is more like six, seven percent of emissions. Steel is another seven or eight. But like, industrial emissions are really hard and it's not clear that learning rates will be as fast as our renewables. So that is a big problem.

That said, I wrote a piece for Tech Crunch in 2018 or something where I was really worried about this. And we've made more progress, faster on industrial emissions than I expected those four or five years ago. So, are we going to go fast enough? I don't know. But we're moving that needle and then the other one that's hard and big, we talk about aviation. Steel is four times as big as aviation, right? Like aviation we will solve eventually. But steel and cement are really big ones. But the other one that's really hard is agriculture, forestry and land use, cows and deforestation.

And that one's not growing, really, but about a quarter of all emissions, it's bigger than industrial emissions. It rivals, electricity. And that's going to take a mix of just pure policy work to protect land and finding a way to feed the world's appetite for meat, which is just going to go up. Like, forget about reducing meat consumption, it ain't going to happen. Meat consumption is going to keep going like this and this. So we got to find ways to produce that meat or people think is meat at a way that's cost — And I'm actually not that bullish on alternate proteins either.

I think it's got to be like mostly it's going to be fields like where we grow corn and soy and so on today and wheat and animal agriculture is my guess. We've got to find a way with a cost perspective to reduce that cost, reduce the emissions, reduce emissions of things like fertilizer 96% of emissions and protect land from being converted from forest or wetlands into crops or grazing land. And that one, cows and steel and cement keep me up more than electricity and cars.

David Roberts

So, what is happening in steel? You say we're making more progress than you thought. What is the solution that you —

Yeah, I think with steel, the most likely solution is power to hydrogen. Like a lot of the steel emissions — so for recycled steel ... use electric arc furnaces, you can power them with renewables. But for primary steel, we use coal as a reducing agent. Iron ore has oxygen on it. You got to strip the oxygen off. So we're using the coal. You can bust the coal. You get carbon monoxide. It binds with oxygen and strips it off. It's a reducing agent. So you can use hydrogen for that. And hydrogen does look like it's going to have a sharp production.

Ramez Naam

It's not the only bet. There's other bets, I think, breakthrough invested in a company that does a form of electrolysis to extract pure iron that you can use to make steel from iron ore. So there are multiple technology pathways in each of these. But right now, hydrogen looks like the best bet, I'd say, for steel.

David Roberts

Well, let's talk about hydrogen for a second then, because this is like, as Amy said earlier, everybody, hydrogen is on everybody's tip of everybody's tongue. It's the next belle of the ball. Everyone loves it. Everyone thinks it's going to do everything, and you can technically do everything with it if you wanted to. This gets back a little to one of my original questions, which is how far electrification is going to go and how much you're going to need other stuff.

Ramez Naam

Yeah.

David Roberts

How big of a role do you see hydrogen playing in the final analysis?

Ramez Naam

Hydrogen could be enormous. It could be that we build as much power gen, as much renewables to produce green hydrogen as we do for direct power into buildings and electric vehicles and so on. We'll see. I think there's things that hydrogen is not the solution, as we mentioned earlier, like hydrogen-powered cars and trucks. Forget about it. That's been clear for a decade. That's not going to be cost-competitive electrification.

David Roberts

You saw the Toyota guy now —

So out to lunch. They were so good on hybrids and they just totally missed the boat on electrification.

He's out now doing sort of the falling on his sword thing, apologizing to everyone. And yeah, I mean, it's clear for anybody who doesn't know what we're talking about. Toyota's, it was one executive, I think it was like the legendary longtime head of Toyota was like, electricity ishmactricity, it's going to be hydrogen fuel cells. And just clung to that.

Ramez Naam

And that was a unique Japanese thing. Like Japan as a country has made some interesting on paper bets on hydrogen that just don't make any sense. Importing hydrogen across oceans. Hydrogen is so hard to move.

David Roberts

Mixing hydrogen into your natural gas in your natural gas pipelines.

Ramez Naam

Yeah, that might work for just distribution of the hydrogen pipeline. It is the only cheap way we know to move hydrogen today. Or using the hydrogen to make steel, for instance that you then ship round the world. But hydrogen for building heat doesn't make any sense. Hydrogen for cars doesn't make any sense. But hydrogen makes a ton of sense for steel making, maybe for high-temperature industrial heat. Hydrogen makes a ton of sense as an ingredient to make electrofuels. You can put it in existing ships and planes, whether that's ammonia or a drop-in kerosene, we'll probably never make hydrogen-powered planes.

They don't make any sense. But making a drop-in fuel from hydrogen that you can burn in existing Boeings and Airbuses does potentially make sense. And hydrogen for green fertilizer, fertilizer is already like, I don't know, a $70, $80 billion market for hydrogen goes into methane-based hydrogen for fertilizer on the world today. So that's already like an enormous market that once hydrogen gets cheap enough, it has various access to.

Yeah, everybody should listen to the pod I just released this morning I think. I'm not sure when this will come out, so this won't mean anything to listeners, but my last pod, a guy whose business model is off-grid renewables, feeding directly into electrolyzers, making green hydrogen, which then go directly into methanol. They're starting with methanol for ships. None of it's connected to the grid, no pipelines coming in or out. The only thing that comes out of the whole thing is trucks full of methanol. It's really interesting —

It makes a ton of sense. It's way easier to move hydrogen as a product that's not hydrogen than it's hydrogen itself.

David Roberts

Right. That was his calculation. His calculation was it's really difficult to move hydrogen and it's really difficult these days to move electricity. So let's move the methanol. Let's make methanol and move it.

Ramez Naam

I will say that the policy details about hydrogen were mentioned in the earlier panel and there's a big policy fight right now of what gets counted as clean electricity for hydrogen. And there's every chance we're going to screw it up. And that the IRA is going to be interpreted by the treasury that actually controls who gets the tax credit to just let you buy grid electricity and unbundle directs, which are kind of BS, as a way to call your hydrogen green. And if that's the case, it's going to set us back for a while and we'll see how the treasury rules. But it's not looking that pretty.

David Roberts

Although, it's worth saying that it says not to get into this whole thing, but it says in the statute that the hydrogen subsidies must reduce emissions. So if they do it that way, it won't reduce emissions. So I don't see how they get around that very plain statutory language, although I'm sure if they tried hard enough —

Ramez Naam

I'd love to be wrong. I hope that you're right.

David Roberts

And another big battle going on around hydrogen that's maybe just worth calling out is natural gas. Companies that are dying, looking at obsolescence, flailing about for some reason to stay alive, are now talking about mixing hydrogen in with natural gas to lower the greenhouse gas intensity of the natural gas, which is just somebody compared it to pouring champagne in your municipal water supply or something like that. Just the most ludicrous use of hydrogen possible. But there's a lot of money, a lot of money behind that one. Now so a lot of opportunities for shenanigans around hydrogen.

I want to ask a bigger theoretical question, because this is one of my favorite things to talk about and I'm never sure how seriously I take it, I'm never sure how serious I am about it. But when you look forward at the solar cost curve, it was ludicrously optimistic back in 2011. If you just do the same thing today, once again, like ten years out, it's just ludicrously cheap. It's just cheap beyond anything anybody knows how to process today. Wind, too, and batteries too, but mainly solar. You had a great chart about batteries, which just made the point that as they get cheaper, you find more uses for them and as you find more uses for them, they build more and they scale up and they get cheaper, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

Same for solar. Like as it gets cheaper and cheaper and cheaper and cheaper, it's just going to be possible to put it everywhere, on everything, all the time. And so you can see in the distant future, but our lifetimes, I think a society in which power is ubiquitous and to coin a phrase, too cheap to meter, is that going to happen?

Ramez Naam

I think we'll always have a reason to pay for it. And as the cost goes down, appetite might go up. You look at other things, like the cost of lighting has dropped by a factor of 500 over the last century, and that's a combination of power getting cheaper, the way they produce lighting any cheaper, and efficiency, LEDs. So will the cost of power drop eventually? It will. I think that what you're going to see is right now the grid investment is sapping up most of the reduction in cost of renewables, and the cost differential of power across time and space is going to change.

What I mean by that is today power costs do fluctuate by season and by location, but fossil fuel costs vary less. Whereas in the future you're going to find is like, how do you power stuff in winter, especially a place far away from the equator. So the power cost average of the year might be cheaper, but in January, like in the UK, in London, you get one 7th as much power from solar panels in January as you do in June or July. So that means that the cost of power from solar at least is going to be loosely high in winter.

And guess what? UK energy use, or Germany's peaks in winter. So I think you might find much cheaper power in certain times and places, but not as much in northern latitudes in winter. And that's going to cause funky things in sort of our power pricing. That having been said, I think there's every reason to believe that in the long run, energy is going to be cheaper for people than it is today, certainly as a portion of income.

David Roberts

Yeah, I guess I just wonder if you ever can imagine it becoming cheap enough and ubiquitous enough that we get to something like elevated global standards of living and fully autonomous luxury communism or whatever you call it.

Ramez Naam

Maybe. I mean, we're getting more elevated standards of living around the world today. People don't know this, but global inequality peaked in the 1970s and has been dropping since then. If you compare countries around the world, and not just within one country, poverty has dropped massively. So the number of people on Earth that don't have electricity access has dropped materially in the last 10 or 20 years. The number of people without access to clean water and food has dropped a lot in China and India, less so sub-Saharan Africa. So we are gradually increasing global abundance. Are we going fast enough?

No, but it's happening, and I think there's every reason to believe that it will continue to happen.

David Roberts

So let's talk about fast enough then, because obviously the counterweight to fully automated luxury communism is climate dystopia. Who knows how those might balance out? What fun? What fun? We'll all find out.

Ramez Naam

It's good for science fiction.

David Roberts

Yeah. So, I think it's clear though, that even with all the good news these days and all the momentum behind clean energy, and I think growing momentum, you could say it looks pretty clear that we're not going to hit our 1.5-degree target that we all agreed on in the UN. Not at least through the replacement of fossil fuels with clean energy alone. So, I think that people say that a lot and then there's a sad trombone and everybody's sad for a while and then we move on. But it seems like that's important and we should be thinking about what that means, what to do with that information, what we should do.

Are there emergency pull handles, if emergency type things we should be doing when we think about avoiding 1.5 or trying to keep to 1.5 or compensating for not hitting for 1.5? So, how do you think about sort of if you think of the energy world as kind of going the right direction but not fast enough, what do you do about the rise in temperature in the meantime?

Ramez Naam

It's a great question. Just like to put some numbers around that. When you and I both sort of got into this field, 2011, let's say we thought the world was headed for four, five or six degrees Celsius of warming. And that's the difference between now and the middle of the last Ice Age. That is truly the stuff of nightmares. That is like agriculture would fail in various large parts of the world. Probably not an extinction level event, but maybe the end of human society in certain ways.

David Roberts

Yes. I never forget Kevin Anderson's quote, "Four degrees is incompatible with organized global society."

Ramez Naam

It ain't good. Right. So the good news is we have very likely canceled that apocalypse. Like if you look at what's happened now, just in the last 24 months, we had a raft of papers saying the most recent one says the most likely outcome, there's climate dice, there's probability distributions. There's lots of unknowns in this. Most likely outcomes now are, I think the most recent papers had 2.1 and 2.4 degrees Celsius of warming. And so the good news is we should all celebrate that for a while, because that is a level of temperature that is actually compatible with the world overall growing richer.

We've canceled — like, it's no longer going to be what's the movie where you have a new ice age come in, whatever — any of these day —

David Roberts

Day after tomorrow.

Ramez Naam

Day after tomorrow. We're probably not headed for that right now. So let's take a moment to actually be happy.

David Roberts

And that movie had an ice age literally coming, like, block by block. There are people running away from it.

Ramez Naam

That'd be really bad. But the bad news is we have missed 1.5 degrees C. And I don't know how to say this anymore, clearly, because there are people that will tell you that we might hit it. The odds of that are minuscule.

David Roberts

You can still torture a model to get the model to show us hitting it.

Ramez Naam

The carbon budget, the remaining budget. The most recent papers, like, from last month, say that the carbon budget to have a 50-50 shot of staying below 1.5 C is about 250 gigatons. We're emitting about 50 gigatons of carbon per year. So that's five years of emissions. Or if we smoothly went from 2020's numbers to zero in ten years, by 2032, we'd have about a 50-50 chance of staying below 1.5. That ain't going to happen. Okay? Like, it is just not a thing. Now, the good news is to stay below two degrees C is about a trillion tons.

That's about 40 years of emissions. So it's about a little over 20 years of emissions. If we had 40 years to reach zero, you have a 50-50 chance of two degrees C. That's a stretch. 2062. But it's not impossible.

David Roberts

It's a stretch.

Ramez Naam

And 2.5 degrees C is more than 2 trillion tons. So that if you, like, smoothed out from today to net zero in 2100, you do a 50-50 chance, the models tell us of staying below 2.5 degrees C, and that is totally achievable. That's the good news. Okay, what's the bad news? So first, like, at 1.5 degrees C, the world does not end. It doesn't end at 1.6 degrees C, but every tenth of a degree matters. And right now, for instance, most recent papers say that every coral reef on Earth above 1.5 degrees C will experience bleaching events more rapidly than they can recover from.

They won't all die on day one, but they'll just enter a period of permanent decline. Now, the planet's going to be fine after the last mass extinction event. It took about 4 million years to recover biodiversity in the oceans. That's nothing to the planet, but it's forever for human civilization. So our children and their children will not live in a place of such abundance. Okay, so what can you do? I've started to say that there's three things we can do on climate. Number one is build. That's what we just talked about, getting out of the way of permitting, having more policies to build stuff, so on.

Number two is help nature adapt. And I'm going to say the things that are like my most provocative things. Maybe you're not going to like me after this, but I'll just call it how I see it. There is no such thing as wilderness on planet Earth anymore. We have modified the climate such that if you're if it's a forest, if it's a coral reef, if it's a wetlands, it doesn't exist in the same climactic band that that natural ecosystem evolved in. And so if you want to preserve those, we have to actively manage every so-called wild ecosystem on Earth, whether that's a rainforest or a forest in the Northwest or in Canada or in the tundra or things like coral reefs.

And there's ways we can do that. But we have to get off of this naturalistic fallacy of like, we should just leave nature alone. You leave nature alone, it's going to die. Right? The only way to do this is we know there are some coral species that do better in high temperatures than acidity. Nobody wants to genetically engineer them, but you could be selectively breeding coral species for maximum survival rates in high temperature and helping these coral reefs adapt so that they can survive. So that's one, and then the next one is the even more controversial one is we've already geoengineered the planet.

We just have. We've done it accidentally through carbon emissions, and we've also done it by things like when people talk about solar radiation management, this is scary kind of geoengineering. We're talking about reflecting more sunlight into space, cloud brightening, or injecting aerosols into the stratosphere to reflect a tiny bit of sunshine back into space. Nobody wants to do that. Okay, but let's be clear. We're already doing that, and we're undoing it unintentionally. Today, if you look at IPCC's numbers, all greenhouse gases account for about three watts per square meter of warming. That's human activity. The sulfur aerosols we're already emitting from ship fuels, from diesel engines, from coal plants, low altitude, they cause acid rain and other nasty stuff.

That's about one watt per square meter of cooling. That's already a solar shield with huge air bars, bigger air bars than greenhouse gases. And guess what? We're undoing that. In 2000, the International Maritime Organization's new IMO regulations went in that reduced the sulfur content of ships. And that means that we're in for this bonus warming where we're undoing our solar shade and we're going to have more warming happening. You see it. You're going to see some satellites, shipping lanes having less reflection and more sunlight being captured.

David Roberts

Yes. This is an irony that is not well understood in the public, I think, is that by cleaning up air pollution, we are pretty radically accelerating warming.

Ramez Naam

So James Hansen and James is a little bit of a radical scientist, but he's got a paper out. He's really, really worried about unforeseen bonus warming as we cut these sulfur aerosols. So should we just start injecting some into the stratosphere? No. What? We ought to do some science. So, last year, before the IRA, the world spent about $1.1 trillion on climate tech. $1.4 if you ask the IEA, that's one times ten to the ninth. The total budget for all science into solar radiation management has been about $10 million. Right. Like one times ten to the seventh.

Right. I think I've had a factor of three off there. Sorry, ten to the twelfth versus the seventh. That's 1/100,000th. As much we spend on just doing, like, computer modeling and small experiments. And so I'm a modest man. I don't think we should spend a lot of money on this, but let's spend a billion dollars a year. That's nothing. Americans spend $4 billion a year on shampoo, so a billion dollars is not much. It's like chump change. A billion dollars in climate gets you nothing. But let's spend like a small amount, a billion dollars a year on actually doing the science.

Better computer models, more compute time, more funding for scientists, platforms that have sensors. When the next volcanic eruption happens, it sends stratospheric aerosols up. We can send LiDAR and spectrography and so on through them and see what happens. And some small controlled experiments, tiny ones, to actually see how this works. Just to know, do we have this tool in our toolbox so that we could deploy it? If the Arctic starts to warm exceptionally fast, we have uncontrolled methane release. And if we're not doing that, I think that's criminal. And that is the single biggest problem that we have in climate tech, the single biggest omission that we have in our climate plans today.

David Roberts

So when I think about those things —

Ramez Naam

Like, no one's throwing a tomato at me yet.

David Roberts

Everybody's still chewing on it, when I think about these things, one of the things I've learned over the course of my career is that lots of ideas sound good if you can sort of stipulate a rational humanity to do them. But it turns out that's a large stipulation and in fact, we don't have one of those, and in fact, we screw everything up. So I'm just trying to imagine humanity as we currently know it with our current leaders and our current institutions trying to manage every global ecosystem, and my mind turns to various horrors.

Ramez Naam

And it could be horrific. But let's bear in mind, we're just doing it now on accident. So we have this status quo bias of like, oh, as long as it's accidental, it's fine for us to play God. But you know, like, God forbid that we start like, doing it with a plan. And some of these things like solar radiation management are so cheap that Bill Gates could afford to just do it on his own. He's not going to. But if we don't do the science, then somebody's going to do it without having data on what the effects are. So I think that's more irresponsible than actually understanding it.

David Roberts

Yeah, I think it's in the book The Deluge, which maybe some of you guys have read. I did a podcast on it a while back. I don't know if you've read it. You really should. You would love it. It's an effort to sort of play out climate politics for the next 40 years. And one of the chapters of that book is about India rogue solar managing and leading to causing a war, basically like an invasion.

Ramez Naam

And Kim Stanley Robinson had a plot like that in Ministries of the Future as well. It's something that any small country basically could afford to do.

David Roberts

Yeah. Crazy. Okay, I quasi deliberately left about ten minutes for a spontaneous Q and A. So if anyone has questions for me, please say so.

Audience Member

I have a question. So you talked about the deep stuff with we're not likely to meet the limit to 1.5 and all that. I've been thinking a lot about options to phase out fossil fuel infrastructure potentially early to get rid of locked-in emissions, which is causing a significant chunk of that problem. So this could be a range of different options from phasing out coal plants early to creative options to get people off this sort of dependence I don't really want to bring up here. But what are your thoughts on that area in particular in terms of how much it can at least make a difference towards limiting damage overall?

Ramez Naam

Yeah, I would say overall I'm less of a cut-off supply person because so often if you cut off supply in one place, somebody else produces it and routes around it. Right. If you like, Shell sold all of their oil fields in the Permian. Guess what? They sold them to Exxon or somebody who just produces the oil anyway. So like divestment is also it's a hard sell to me that having been said that we should try many things. And so some of those successful policies have been policies that worked with local communities. The Sierra Club's Beyond Coal campaign funded by Mike Bloomberg worked with local communities to shut down coal plants early and to find jobs for the people that worked in coal mines working these coal plants, replace them off with natural gas, with renewables and so on. Sometimes —

Wildly successful before it was cool, by the way. Shout out to Sierra Club.

Yeah. And so I think you can have creative stuff. But as Jessyn was saying in the previous panel, you got to have buy-in from the community, from other stakeholders, to get that sort of model built, I think.

David Roberts

What would you say if I can inject here, what would you say to someone who said, if you are willing to contemplate something as extreme as humans managing all global ecosystems and managing the atmosphere with SRM, it seems like the chances of those screwing up are high, and it would be worth a lot to avoid them. What do you think about MOM's argument for ecoterrorism?

Ramez Naam

I don't advocate violence. As a science fiction writer ecoterrorism is very exciting because you can, like, you can write a plot, a thriller plot around — it's hard to write a thriller plot around climate in general. But in reality, would it work or would it have negative effects or blowback? I really don't know. But one of the reasons to do the research on things like SRM is to reduce the need for someone to engage in ecoterrorism. And so I think that's worth thinking about.

Audience Member

Hi. Big fan of the podcast. I absolutely adore it. My name is Ben Riley. We've gone beyond just simply the energy transition. My question is related to that, which is the role of negative emissions and how do you feel about various forms and what role it has to play?

Ramez Naam

Yeah, so again, I'm somebody who's a believer in let's build more tools than we think we might need. And I'm a big tent person. Like, I'm dubious on nuclear fission, but I'm like more power to it. Let's invest in it. Let's change the NRC, make it easier to build stuff and so on. That's more or less how I feel about CDR, too.

So, personally, my bet is permanent carbon removal is just too expensive. To cut temperatures by about a tenth of a degree C, you've got to cut carbon emissions by 100 billion to 200 billion tons. And so if you're talking about $100 a ton carbon removal, you're talking about 10 or $20 trillion. And that's real money, and that's how you get to $100 a ton. So personally, I'm really excited that Stripe, Microsoft, and Google are committing billions of dollars to carbon removal advanced purchases. They've learned a lot from learning rates and so on. It's modeling up that off what we learned in solar, and I think more power to them.

But I'm not making any bets in that sector because I just don't see, like, if you tell me that carbon removal could get down to, like, $10 a ton or $5 a ton, I think it might be a big part of the solution. But at $100 a ton or $50 a ton, I just don't think the world I think there will be multibillion-dollar markets. You'll have some people make a lot of money. Some venture capitalists will do well, some ... will do well, and it won't move the needle is my personal bet, but again, I'd love to be wrong.

Audience Member

So David and Mez, you've both expressed sentiment that we have sightlines to decarbonizing most essentially of the economy and that clean energy is cheap and it's getting cheaper and that it's going to outcompete fossil fuels in a lot of applications. But I'm curious about the possibility and what you see as the potential that we get most of the way there and then we get to the really hard parts and things kind of stall out in terms of the political will to accept the high cost of getting to a completely decarbonized future, which we need to get to to actually halt global warming. Because although clean energy is cheaper, probably for a lot of applications, it's questionable that an economy that uses exclusively clean energy is going to be cheaper than one that uses clean energy and also has the option to use fossil fuels where they're most cost-effective. So curious for your thoughts on that.

Ramez Naam

You want to take that one?

David Roberts

Yeah. I mean, it's an interesting conceptual question about how you think about the transition. Whether it is like a boulder rolling down a hill, gaining momentum and momentum, momentum such that it will just crush and go right through the last bits, or whether you're eating the fruit off the tree that's lowest and you have to climb higher and higher and it gets harder and harder and harder and harder. And I think there's a little bit of both. But I'm so curious what you have to think.

Ramez Naam

I think of it as we're on an S curve, right? And it's like renewables, let's say, just in power solar and wind are 13% of global power generation, they are entering the decade where they might have the fastest growth and we're going to see the growth accelerate. But at some point, they do hit these headwinds of as Jessyn has done, and you've done these like they cannibalize themselves. They suppress prices at the hours that they're operating with the problem of winter. And so you —

Get to more difficult land.

You get to more difficult land for sure. And so you do hit this challenge, whether it's at 60%, 70%, 80%, where it gets harder and harder. And so I do think most like models of decarbonization assume a curve that looks like this. We have the fastest reductions early and then it kind of goes like this. And I think that we're going to see something that's much more of like an S curve where it's going to take a while to hit the peak and then renewable like, emissions are going to drop from some sectors really fast. And then the last bit is going to be really hard and really slow.

But while everyone's obsessed with hitting net zero, if we get to 10 billion tons a year by 2100, that's actually still compatible with canceling the apocalypse. So I worry more — this is to steal a memorable movie quote, I worry more about the next 20, 30, 40 50% than I do at the last 20% right now — although I do think we should invest in more technologies to try to have a head start on those sectors now than we need.

David Roberts

And just one other consideration to throw in there is that as the carbon lobby shrinks, policies to reduce carbon become easier to pass. So when you're targeting a smaller part of the economy, it's a little politically easier, I think, than it was when you're saying, everybody reduce everything.

Audience Member

Hi. So, under the umbrella of hot trends and climate tech, I'm curious about grid enhancing technologies, specifically both on the transmission and the distribution system. I'm curious if there are any things that either of you are particularly excited about and what do you think some of the limitations or challenges are to adopting those technologies and how do we overcome them. So, small question.

David Roberts

Yeah, you want to go first?

Ramez Naam

Go ahead, sure. Yeah, I think it's fascinating. I think like the grid, I talked about permitting and long-range transmission, but interconnection queues and distribution are a more pressing problem. They're a problem for like, hooking up your renewables to the grid at all. They're a problem for things like Jessyn was talking about. How do you build an EV truck charging depot? If you want a system of high-speed chargers for electric semis, that's like a tens of megawatts power drop, that's like a small town. So building that is really hard. And the grid is not used to working fast.

I'm a big fan of software control of power generation and consumption. There's lots of startups that are doing interesting things to make more efficient use of the grid. Storage at the grid edge, I think, can do a lot to make better use of the current system. And then you have some other crazy ideas. For instance, a friend of mine did her dissertation on taking high voltage AC transmission corridors — assume that you can't build more transmissions of permitting, but upgrading the power electronics on current corridors from AC to DC and you could get — this is Liza Growing — you could get triple or quadruple the power on this existing rights of way. So I think there's solutions like that that are probably still under invested in or there's Veir, it's like a superconducting tape you apply to — I don't know if that'll ever work, but that one would be cool. You can apply it to current transmission lines and again, massively increase the power on them. So I think there's room for a lot of creative solutions.

David Roberts

Yeah, I don't think people get that on a lot of these big long-distance transmission lines. A lot of our big transmission lines, they run at like 30% capacity, like 30, 40% capacity. Just because we need a big buffer, because we don't know in real-time what's happening on that line. This gets to a larger theme, which I just was mentioning on a podcast earlier, which is I don't think people appreciate, especially people who grew up around the Internet and people who view information as sort of like modular and transmissible everywhere and everything. People think of the grid that same way, but I think people would be shocked to hear how much of the grid operates by people turning knobs and making phone calls to other people like, "Hey, you should probably use less power over there."

It's weirdly primitive how we run our grid now. And that's not a technology problem. There's all kinds of grid-enhancing technology. There's all kinds of ways to get a lot more out of the existing grid and just generally moving towards digitizing the grid. To me, the barriers there are almost 100% sociopolitical, it's almost 100% utilities, which is you pull any string in this mess long enough and you end up back in utilities. It's utilities not being on top of things. So I think that's on the one hand, that's very frustrating, but on the other hand, I think that could change quickly if we ever get utilities in hand.

Ramez Naam

Fix their incentive model.

David Roberts

Yes, I know it changed. We don't have to get into the whole utility mess. But yeah, that's 100% about just procedures and regulations and things like that more than technology.

Ramez Naam

I think that was the execution of the death sentence.

David Roberts

I think we're done.

Ramez Naam

Thank you all.

David Roberts

Oh yes, okay, so we're done everybody. Thank you for coming.

David Roberts

Thanks.

Ramez Naam

Give money to Canary.

David Roberts

Thank you for listening to the Volts podcast. It is ad-free, powered entirely by listeners like you. If you value conversation like this, please consider becoming a paid Volts subscriber at volts.wtf. Yes, that's volts.wtf so that I can continue doing this work. Thank you so much and I'll see you next time.

What's next for clean energy and climate mitigation